|

|

|

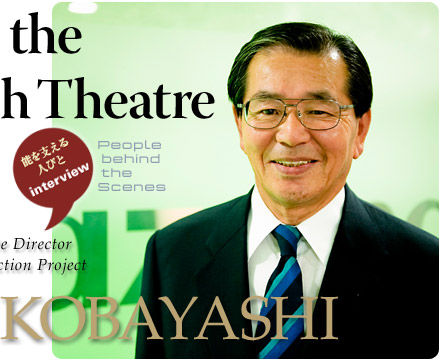

| | Home | People behind the Scenes | Shigeru Kobayashi |

| |

|

|

|

|

Photo: Shigeyoshi Ohi |

In 2008, various events were held at the National Noh Theatre (Sendagaya, Tokyo) to celebrate its 25th anniversary. One of them was the screening of a video entitled “National Noh Theatre.” It records the efforts that went into building the National Noh Theatre and introduces the advanced design idea, amazing skills and select materials used therein. The National Noh Theatre, the centre for multiple schools of Nohgaku, holds many surprising secrets.

We wanted to know more about the National Noh Theatre construction project. Our curious editorial staff tried several different approaches and were eventually able to speak with the site director of the construction of Hazama-Sumitomo JV*, Shigeru Kobayashi (formerly of Hazama Corporation), who also appeared in the video.

Mr. Kobayashi, who made time to meet with us on two occasions, is extremely pleasant and gave our staff a very understandable and kind lecture. Each part of the National Noh Theatre is filled with the passion and hard work of those involved in the construction.

*Hazama-Sumitomo JV: Joint venture between Hazama Corporation and Sumitomo Construction (currently Sumitomo Mitsui Construction). Hazama Corporation served as the lead company in the National Noh Theatre construction project.

Challenged by a New Experience

|

|

National Noh Theatre Photo: Shigeyoshi Ohi |

“Acting as the site director for the construction of a Noh theatre, and more than that, the one-of-a-kind National Noh Theatre that welcomes all schools, was honestly quite challenging.” (Mr. Kobayashi, same for below parentheses)

Shigeru Kobayashi spoke openly with us about how he felt while working on the project. While he had worked on castle construction before, this was his first time working on a Noh Theatre. His father had studied utai in the Hōshō School, but he had no real connection to Noh. And this was a government project. The responsibility of leading the project turned into pressure.

“But the head of construction encouraged me, telling me to ‘go and do a good job.’ So I got motivated and set high goals for a construction project that would be unique to the world. I visited the Kanze School Noh Theatre in Shibuya, Tokyo, looking both for information, inspiration and motivation.”

The National Noh Theatre construction project started in 1976 (Showa 51). It began with the launch of the Construction Preparation Evaluation Committee. The land was purchased in 1979 (Showa 54). The controller of the project, the Ministry of Construction (the current Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism) accepted bids, and Hazama-Sumitomo JV won the contract. For Hazama, who had demonstrated its abilities in the restoration of traditional Japanese buildings such as Meiji Shrine, Aizuwakamatsu Castle, as well as other temples shrines and castles, this was recognition of its accomplishments. The head of design was a star architect who was an authority in both modern and traditional construction, the late Hiroshi Ohe (1913-1989). Construction by the Ministry of Construction, the Ohe Construction Office and Hazama-Sumitomo JV officially began in May 1980.

The selection and handling of the most important Japanese cypress tree

|

National Noh Theatre

Photo: Shigeyoshi Ohi |

To realize high goals, one must start with the best materials. For the stage on which the actors dance and the floor of the hashigakari, the finest Bishu cypress was used. First wood from 400-year-old trees with no knots and uniform colour was selected, then the very finest pieces were selected from among these.

“Even pieces with spots of resin of only a few millimetres were removed, leaving only the very finest wood. This was actually the task we struggled with the most. At the time, 1m3 cost 12 million yen, and since the records show that we used 5m3, the stage floor alone cost 60 million yen. I wonder how much it was including the wood we rejected. Of course it was used for other construction projects and did not go to waste.”

Since the other parts went way over budget, we were forced to give up using domestic lumber. For the beams, joists, steps, rafters, main room and study stage, 2000-year-old Taiwanese cypress were used. For these, we have records of using 130m3.

“I flew to Taiwan myself and went to the Alishan area to venture into the old-growth forest myself. I made sure everything was ok in the storage area after the trees were cut and oversaw the selection of the wood at the processing site. By comparison, the Taiwanese cypress are more red than Japanese trees. It was difficult to find wood that was similar to domestic lumber.”

During construction also, we gave the utmost care to the handling of the cypress. Just the oil from one’s hands from handling the wood would damage it greatly. The workers wore both gloves and tabi, Japanese socks, when handling the wood, and it was stored with thorough care so visitors wouldn’t mistakenly touch it with their bare hands.

“Since this was a national project, representatives from the Ministry of Construction, people from the construction industry and everyday citizens came to visit from around the country. While we were thankful for the visitors, were also very nervous to make sure they did not handle the wood. We made sure that they looked from as far away from the stage as possible.”

The roof of the stage is made of hiwadabuki (a roofing technique unique to Japan in which the bark of the Japanese cypress is layered), a portion of the Kenjo uses a similar technique kokerabuki, and a technique unique to traditional construction using bamboo nails is also employed.

“The hinoki bark and kokera come from an area called Tango and Tanba, but materials of that quality are probably hard to come across now.”

Understanding the vision of the designer and making it a reality

|

The Late Hirsoshi Ohe During Construction (to the right in the front line) surrounded by project members. Third from the left in the back row is Shigeru Kobayashi (Source: Hazama Corporation) |

|

Panoramic view of the National Noh Theatre after Completion (Source: Hazama Corporation). |

The designer of the National Noh Theatre, Hiroshi Ohe’s father was Shintarō Ohe (1876-1935) a leader in traditional construction who was involved with the restoration of Nikkō Tōshō-gu and the construction of the Meiji Shrine Treasure Museum. In addition to producing modern buildings, he was also actively involved in utilizing the styles and designs of traditional Japanese construction. On designing the National Noh Theatre, he said, “I wanted to appeal to the sensibility of the Japanese people of today by allowing the good qualities of modern construction to be experienced together with the taste of traditional Japanese construction”. Amid a tense relationship between the two, Kobayashi attempted to realize Ohe’s design vision and methods in the construction process.

“We called Mr. Ohe the “grand master.” Grand master Ohe had a great respect for the spiritual, and would often say that spirits resided in the trees. And since ancient animism flows through Noh, he would often say that creating an appropriate place for that quality to be realized was important.”

“While I have many memories of him, I will never forget going with him to see the Noh stage at Nishi Honganji in Kyoto. I was able to visit a stage that is an important national treasure and hear him explain it, and was even allowed to step on stage. I had the opportunity to see one more stage in Kyoto. We also stopped off at Nagoya to participate in a party hosted by many important friends of the grand master, and I again realized just how great he was.”

Ohe’s design was extremely delicate, and the beautiful curved lines are known as the “Ohe Style.”

“For example, if you look at the lines under the roof, they appear straight, but both ends are actually raised. The traditional Japanese construction technique of raising both ends makes the line appear straight. These lines and the other curved lines used by Ohe have a very unique soft nature to them.”

In typical construction plans, details are gradually added onto the design of the frame until eventually the design is complete, but Ohe started with a sketch of the idea, then envisioned how to design it and worked backwards to the design of the frame.

“It was a tough job for the construction plan staff. There were five or six staff members working in shifts. Without changing the frame construction, they worked to build a design that made full use of the Ohe Style.”

In numerous interviews, Ohe repeated that he wanted Noh, with its austere image, “to be seen in as liberating and welcoming a space as possible, while respecting the ‘personality’ of the traditional art” and that he had “taken care to create a design that helped draw the audience naturally into the world of Noh.” While the construction of the National Noh Theatre, with all of its special visions and designs elements, was very difficult, Kobayashi is very nonchalant.

“What we struggled with was the selection of the lumber and drawing the construction plans, after that it was just a matter of infusing the passion of the Ministry of Construction (the current Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism) and grand master Ohe for this important project with kind instruction and cooperation to smoothly execute the construction.”

Tension throughout the worksite

|

Construction of the National Noh Theatre (Source: Hazama Corporation) |

Listening to Kobayashi, the fact that he makes such a difficult task seem like a breeze made us think that there must have been a sense of tention on the worksite.

“When the actors dance on a Noh stage, even the slightest cough is audible. The same tension exists on the worksite. You feel like you can hear even a splinter dropping.”

The presence of highly skilled craftsmen also added to the atmosphere of the worksite. The construction staff of Ha-Sumitomo JV approached their work with the high sense of professionalism Kobayashi expected. The staff included temple builders, master carpenters.

“To include traditional Japanese construction techniques, we had temple builders from two companies lead the carpentry. Master carpenters from Osaka handled the stage area, and the area from the entrance was handled by master carpenters from Nagoya.”

“Working together with them, I remember being very impressed by how carefully the temple builders cared for their tools. They spent so long sharpening their planes and drills, and I thought they were just wasting time and that they should hurry up. But the high quality of the tools produces through the sharpening made them able to demonstrate their high-level skills. Without these expertly sharpened tools and skills, the superior Japanese traditional construction could not be realized. Japanese carpentry is truly an art. While much of the style itself originates in China, it was our ancestors that refined it through their expert skill, and the master carpenters who preserve it.”

Lucky as builders

|

In September 1983 (Showa 58), a National Noh Theatre commemorative stamp was issued (depicting Shigeru Kobayashi). |

On August 30, 1983 (Showa 58), roughly two years and four months had passed since the start of construction and the National Noh Theatre was complete. Kobayashi’s construction team had worked more than 1.6 million hours accident free, and received an award from the Tokyo Labour Bureau for their track record.

“Everyone including master Ohe’s design team, the construction staff and the Ministry of Construction who managed the project worked together to ensure a priority on safety on the worksite.”

In October 1985 (Showa 60), two years after its completion, the National Noh Theatre was awarded the Building constructors Prize, honouring the owner, designer and builder. The National Noh Theatre was special, even in the eyes of construction professionals.

“Only a select few in the construction industry can work on a historic building like this. There were less than 20 members of the construction staff from Hazama, including those responsible for drawing the plans. It was really a blessing to participate in what could truly be called a once-in-a-lifetime project. I feel very lucky to be involved in the construction. I think everyone involved feels the same way.”

Around September 15 1983 at the opening ceremony, the heads of the three main schools, Motomasa Kanze, Hideo Hōshō and Minoru Kita performed Okina and Yumiya No Tachiai as the first plays performed at the theatre. After that, the National Noh Theatre became a centre for performances by all schools of Noh, an instructional centre for Noh actors, a research center with abundant materials, a display area for the things of Noh and an overall centre of activity for the art. Kobayashi took the time to take in a performance of Noh.

“I like action, and Dōjōji is one of my favourites. I also like heroic shuramono like Yashima.”

But he pays attention to more than just Noh when at a performance, looking at both what is on stage and off.

Looking at Kobayashi’s face as he asks “Does it smell like Japanese cypress now?” I see the expression of a kind father speaking of his child. (August 21, 2009)

Accompanying the interview, we present rare photos of the gakuya and kagami no ma of the National Noh Theatre not normally made available to the public for you to enjoy together with commentary from Shigeru Kobayashi.

Profile : Shigeru Kobayashi

Born in Tokyo in 1939, Kobayashi graduated from the Nihon University College of Science and Technology in 1962 and joined Hazama Corporation. After working primarily on construction sites in Tokyo and in the Construction Management Department, he worked as the Site Director for the construction of the National Noh Theatre from 1980-1982. In 1985, he was appointed head of the Construction Department of the Yokohama office, in 1987 as head of the Sales Department, and in 1991 as head of the office. In 1993 he was named director, after which he became Vice President of the Construction Coordination Division. In 1999, he retired as director.

Note: Hazama Corporation supports the annual outdoor Noh festival held at Meiji Shrine, also assisting with assembly of the stage.

| Terms of Use | Contact Us | Link to us |

Copyright©

2026

the-NOH.com All right reserved.