|

|

|

| | Home | Great Masters | Kita Roppeita |

| |

|

|

| Shinsaku Hōshō | Kingo Misu |

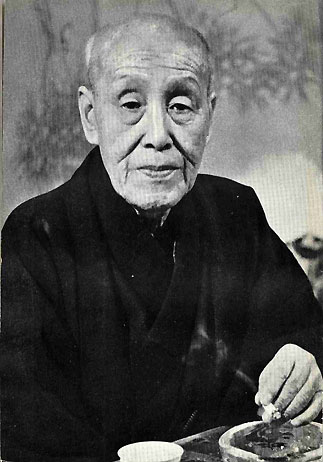

Kita Roppeita XIV (Nōshin) (1874-1971)

A Giant with Small Body

|

|

© Waseda University The Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum |

It was the good fortune of the Kita school to have Kita Roppeita as the 14th head during the upheaval of the Meiji Restoration. After becoming the head, he saved the school, brought up a number of excellent disciples, and made all-out efforts for the success of the school. We will long remember him as one of the representative figures in history of Noh during the three eras of Meiji, Taishō and Shōwa.

When the Noh schools were at a critical point in their existence after the Meiji Restoration, the Kita school was in especially desperate straits among the shite-kata (lead part). The 12th head Kita Roppeita (Nōsei), who was active in the late Edo era, died in 1869 (Meiji 2). His adopted heir pursued pleasures and disposed of many ancestral items including masks and costumes. Due to his roguish behaviour, the Kita family faced difficulty in continuing their art, and the Kita school was almost ruined. Some of the best disciples had to secure their livelihood by working such as a ferryman or a police officer.

Kita Roppeita XIV was born in 1874, just in the middle of the chaotic period. He was the second son of the head of the Utsuno family, which was a family of former vassals of the Shogun. He was called Chiyozō in his childhood. Chiyozō was one of Nōsei's grandsons because Nosei’s third daughter Matsu had married the head of the Utsuno family, Tsurugorō. As Japanese society gradually recovered composure, some of the best disciples became eager to reconstruct the Kita school. They decided to choose the next head from Nōsei's grandsons, and marked Chiyozō for it because he was not to succeed his native house. Young Chiyozō had his name entered in the register of the Kita family in 1879 (Meiji 12). He made his debut on stage playing a juvenile part in Kurama-tengu in 1882 (Meiji 15).

In the Edo era, not only the Shoguns but also many of the feudal lords loved Noh. From the Meiji Restoration onward, there were many former feudal lords who still loved and supported Noh. Among them was Count Tōdō Takakiyo, the former load of the Isetsu Clan (in present Mie Prefecture), had full proficiency in the art of the Kita school, and rendered great services in restoring the school. He offered time and place to young Chiyozō to practice, and also gave him private lessons. He even played the lead part (shite) in Kurama-tengu, in which Chiyozō made his debut on stage.

In 1884 (Meiji 17), Chiyozō succeeded to the Kita school to become the 14th head at age 10, and performed Sagi for the celebration of his succession to the Kita family. In the programme, Hōshō Kurō Tomoharu performed Mochizuki, and Umewaka Minoru performed Sumiyoshi-mōde. It must have been a gorgeous programme. The following year Chiyozō performed Shakkyō. He learned the piece from Count Tōdō who had been trained by his predecessor. Then he performed in turn Shōjō-no-midare, Okina and Dōjō-ji. After cultivating his ability as a young head master, he succeeded to the name of Roppeita at age 20 in 1894 (Meiji 27).

Although Roppeita was the headmaster of the Kita school, there was no choice but to take lessons from disciples and those in branch families from his childhood, because his school was on the point of being abolished. This situation brought him immense troubles. He later expressed his reminiscences of his unusual circumstances, in which he was one of the very few Noh performers who had so many instructors and struggled with the differences of their opinions, styles and practice methods. However, he also expressed a positive view of such circumstances, in which his technique was both dependent on and independent of each of the instructors, and he neither adapted himself to the old state of things nor followed his own method. He mentioned that he was able to perceive the importance of building his own style and maintaining dignity just because of these circumstances.

When he arrived at manhood, he devoted himself to the pursuit of the art, collaborating in a number of performances with the masters of other schools. He was avariciously and flexibly assimilating advantages of other schools. He did not compromise when any of the elder disciples objected to him. He was especially influenced by Sakurama Banma (Sajin), one of the Three Masters of the Meiji Era. In 1908 (Meiji 41), he performed Utō before the Emperor. He was then highly praised by Empress Dowager Eishō and named as the best performer for the play. Throughout the Taishō era and into the Shōwa era, he polished his performing skills and dignity. He also smoothly trained several good disciples, including the brothers, Gotō Tokuzō and Kita Minoru. Minoru became Roppeita’s adopted son.

He outlived the loss of a stage twice, once in the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 and again in World War II. After the war, when he was in his seventies, he still continued to perform many pieces and won applause. In 1951 (Shōwa 26), he performed Sagi to celebrate his own 77th birthday. He received the Order of Culture in 1953 (Shōwa 28), and performed Okina (Hakushiki) for the celebration the following year. He was designated as an individual holder of an intangible cultural property (commonly called "National Living Treasure") in 1955 (Shōwa 30), and performed Kagekiyo for the celebration. He appeared on stage as the lead part in Part Two of Kanawa in 1958 (Shōwa 33), which was his last performance of a complete Noh piece. He still appeared on stage to perform several dance pieces and some highlights until 1963 (Shōwa 38) when he was ninety. After he quit performing, he was still active in teaching the younger generations, and passed away at the age of 95 in 1971 (Shōwa 46).

Roppeita's unrivalled performance is described in various ways by witnesses. He was less than 5 feet in height. Although he was short, it is said that he looked much larger than his actual size when he was on stage, and his performance was large-scaled. He stood unchallenged in making his performance effective. It is said that he displayed originality in holding the audience spellbound with marvellous and breath-taking posturing.

Roppeita's performances are recorded on film. In one film, the old actor of eighty winters brandishes a sword sharply and moves vigorously on stage. When I saw the film, I admired his power that seemed as if it would overflow from the screen. I wonder how powerful and overwhelming his actual performance must have been.

He compiled the recollections and his views of schools, techniques and performers in a book entitled "Roppeita Geidan" (Treatises of Roppeita). Thanks to the editorial work of his best disciple Gotō Tokuzō and poet Toki Zenmaro, who was one of his trainees in the school, the book is rich in the atmosphere of his way of talking. He also had a dialogue with novelist Mishima Yukio, and overwhelmed Mishima with his discussion of Noh and his own art. Their conversation is found in the collected interviews of Mishima. It is something to be thankful for us that he immortalized the emanation of the modern Noh history to posterity through these documentations.

| Terms of Use | Contact Us | Link to us |

Copyright©

2026

the-NOH.com All right reserved.