Interview

Interview

![]() Part 1: To Pass down Noh over Generations

Part 1: To Pass down Noh over Generations

![]() Part 2: The Era of Zeami

Part 2: The Era of Zeami

Interviewer: Takahiro Uchida, the-Noh.com / Photos: Shigeyoshi Ohi

Part 2: The Era of Zeami

Ashikaga Yoshimitsu used culture as a device to dominate the country

Uchida: You have said that the encounter of the shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358-1408), Kannami and his son Zeami at Imakumano Shrine in Kyoto represented a landmark turning point for Noh. Could you tell us about these three figures in more detail to give us an introduction to the background of Noh.

Kanze: Zeami is indeed a genius. But Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, who appreciated Zeami’s talent and supported him, was also an extremely competent man. Without Yoshimitsu, Zeami would have never become known to the world.

Yoshimitsu was apparently conscious of the failure of Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147-1199) to achieve his ambition of taking over the Imperial court in Kyoto. Learning from this, Yoshimitsu attempted to unite the Shogunate and the Imperial court. At that time, however, with remnants of the Southern court flourishing all over the country, Yoshimitsu found it difficult to rule the nation by armed force. Instead, he turned to culture as a device to dominate the land. First, he created a hana no gosho, or Flower Palace, on what is currently called Imadegawa Street in Kyoto. Instead of building walls, he surrounded the palace with beautiful flowers. It is said that he used not only flowers from Kyoto but also ordered the collection of local flowers by each of the country’s shugo daimyo, or provincial military governors, who later became daimyo (feudal lords). The governors were also told by Yoshimitsu to bring the best flowers from their regions, together with a number of Celadon vases, and to arrange them in a room, dozens of tatami mats in size, at another of his residences, called Kitayama-dai (current Kinkaku Temple), instantly creating a natural landscape. This became known as Yoshimitsu’s hana-awase (flower arrangement contest).

Arima Raitei is chief administrator of the Shokoku Temple School of the Rinzai Buddhism sect and a priest of both Kinkaku and Ginkaku temples in Kyoto. Some time ago, I talked with him at Kinkaku. During our conversation, he told me that the two stones named Ouchi-ishi and Akamatsu-ishi that rise out of the garden’s shinji-ike (lake in the shape of the Japanese character for heart) were tributes from provincial governors called Ouchi and Akamatsu. Yoshimitsu is said to have shown these stones to other provincial governors in an apparent bid to encourage them to present him with large stones, too. As you can see, Yoshimitsu used culture to manipulate local leaders and dominate the country.

Kiyokazu Kanze, 26th grand master of the Kanze School

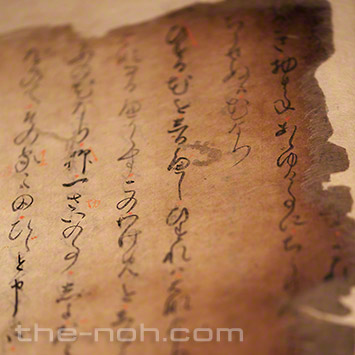

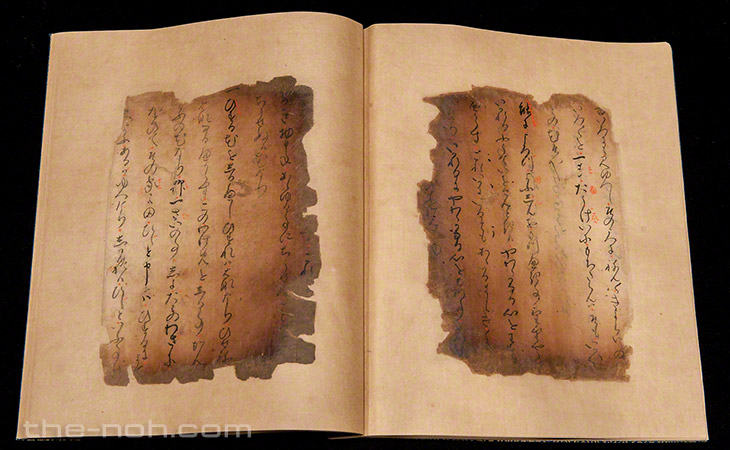

Fushi Kaden, Volume 7, Besshi Kuden by Zeami.

Fushi Kaden, Volune 7, Besshi Kuden, written by Zeami in the middle of the Oei period (1394-1428). It is believed to have survived a fire at the Kanze home in the 16th century.

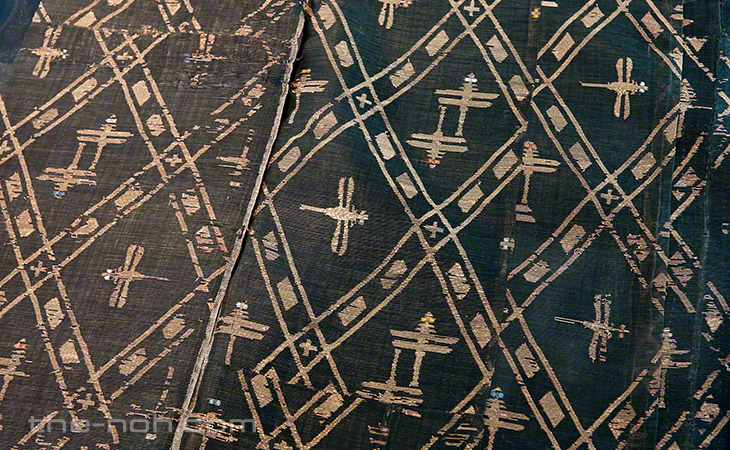

A yellow-green unlined happi (outer robe for a male character) with patterns of diamonds and dragon flies. Onnami, the 3rd Kanze Dayu (head of the Kanze School), received it from Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa. It is the oldest existing costume and was worn only in the play Tomonaga Sembo. It is thus known as the Sembo hitoe (unlined) happi.。

A yellow-green unlined happi (outer robe for a male character) with patterns of diamonds and dragon flies.

Making flowers a theme

Kanze: As shown in tactics such as hana no gosho and hana-awase, Yoshimitsu seemed to value flowers as the essence of beauty. Zeami probably understood this very well and thus chose flowers as the main theme for Fushi Kaden. Volumes 1 to 3, written when Zeami was around 40, focus on a “true flower” to symbolically illustrate the essence of beauty exhibited in the Noh performance. Even so, nowhere in the book can we find any instruction for producing one of these. Perhaps he was unwilling to let people read the secret, but wanted people to learn the secret from the properly disciplined performance. In those days, life expectancy was around 50. Zeami was already a mature Noh actor in his 40s and must have felt that he had already become spiritually enlightened.

When we read Fushi Kaden and interpret its meaning, we see flowers at the foundation – Zeami wondering about the best ways to create flowers and make use of them. Perhaps Zeami devoted his life to resolving these questions. Although Fushi Kaden ends at Volume 7, Besshi Kuden, I imagine he hoped to continue with volumes 8, 9, and 10. One reason he was unable or chose not to write the remaining volumes was that his eldest son, Juro Motomasa, died young. Also, while Motomasa was still alive, Onnami Motoshige, a nephew adopted by Zeami, was appointed Kanze Dayu (head of the Kanze school).

The relationship between Zeami and Juro Motomasa

Kanze: It is said that Zeami and his son Juro Motomasa did not get on very well. The two were divided over whether a kokata (actor in a child’s role) should appear from a burial mound in a scene in the play Sumidagawa. Also, Zeami passed on books of secrets to Motomasa’s younger brother, Motoyoshi, rather than to Motomasa. As third parties, we can infer from these incidents that the father and the son were not really on good terms. Zeami, however, expressed confusion and sadness when Motomasa died.

Were they on good terms or not? Something that complicated their relationship even more was that Motomasa took the side of the Ochi family in the Southern court. The Ashikaga Shogunate, in the Northern court, took a hostile view of Zeami for allowing his own son to side with the Southern court and this may have made it difficult for Zeami to support Motomasa openly.

Zeami returning to Nara

Kanze: Zeami’s life was full of ups and downs, but I imagine that he strongly hoped to return to his home town Nara in the final stage of his life. Hakko Sarugaku at Tanzan Temple in Tonomine is the origin of the Yamato Yoza (four schools based in Yamato Province, or current Nara Prefecture). Zeami performed new plays at the shrine before he left Nara for Kyoto, asking for reviews by armed priests of Myoraku Temple (current Tanzan Shrine). Tonomine in Nara is a transfer point when going from Nara to Kyoto and can be considered to be where Noh performance started. I am currently performing Tanzan Noh myself, under the prodding of Genjiro Okura.

Zeami also started at Tonomine and he must have hoped to return to the place. At the age of 60, he became a priest in Tawaramoto, Nara. I believe this was not because he mourned the death of Motomasa but rather because he wished to go back to Nara.

After he was exiled to the island of Sado, he also wrote about his feelings about his home in the book Kintosho. I believe that he died in Nara, not Sado, although there are no such official records. After becoming a priest when he was 60, he produced Izutsu, Nomori, and Taema.

Kanze is a family of actors that play demons

Kanze: Nomori is a play set in Nara, home for the Kanze (Zeami) family. In the play, a demon holds a mirror that reflects everything in this life, including hell and paradise. Zeami may have longed for such a mirror. Also, by creating the play, perhaps he hoped that posterity would remember Kanze as the Noh family for demons.

Shakki (red demon) and kokki (black demon) masks have been handed down in the Kanze family. Created by a mask-maker called Kasuga, these are extremely deformed and are not used in modern Noh plays. Originally, they were used in a setsubun spring ritual to drive out evil. Once the event finished, the masks were usually destroyed. The Kanze family, however, passed them down in an apparent attempt to leave a message to posterity that Kanze is the family that plays demons and that they should never forget this. Zeami must have aimed to deliver this message in Nomori.

The play Taema, meanwhile, reflects Zeami’s wish to portray the mandala at Taima Temple in Nara. He also wrote Furu, which is about a treasured sword dedicated at Isonokami Shrine in Nara. This sword was said to be appeared in the sky if it detected an injustice, and passed judgement on the situation. Zeami was probably ordered to write Furu after the entire nation was rocked by the death of the fourth shogun, Ashikaga Yoshimochi (1386-1423), in 1423.

Kannami’s vision and education

Kanze: Kannami provided Zeami with a special education. Kannami, who was aware of the talent of Zeami and the importance of education, had an unrivaled talent, too. Initially an actor with Yuzaki-za, Kannami climbed to top position in the troupe with his outstanding skills. Back then, only special actors were allowed to perform Okina. Kannami’s performance of it at Daigo Temple in Kyoto, with Zeami in Senzai (the role of the usher), was a big step forward in establishing the art of Noh.

Zen and Zeami

Kanze: Yoshimochi, who Zeami served after the death of Yoshimitsu, was committed to Zen Buddhism and practiced it enthusiastically, especially the religious rite of confession called kan’non sembo, at Shokoku Temple. There is even a story that Yoshimochi showed up in a room where monks were practicing the rite and strictly reprimanded some of them for failing to read out three important phrases. This shows how committed he was to Zen. His enthusiasm had probably had a great impact on Zeami and Komparu Zenchiku, who both served him. This background helps us understand why, in Fushi Kaden, Zeami responds to a question about what flowers are by saying that there are no flowers. The book ends with this self-contradiction by Zeami. I think this is a typical Zen riddle.

Performing Noh is the most enjoyable

Uchida: I had a great time listening to you. It was like a luxurious lecture.

Kanze: Actually, I would like to have more opportunities to talk about these things with other Noh actors but fail to do this because everyone is so busy, including myself. It’s a shame, because I think it’s very important to share our thoughts.

If there were time machines, I would watch Noh in the era of Kannami and Zeami and see how the actors performed at a time when movements such as suriashi (sliding steps) and kamae (standing posture) had not been established. The plays must have been a lot shorter, too.

Uchida: It took so many years to establish the Noh of today.

Kanze: After the death of Zeami, Noh became a performance for official events, or shikigaku, during the Tokugawa Shogunate. This gave a huge boost to the development of Noh. Some people have said that the art of Noh lost vitality after it became shikigaku, but I don’t agree at all. Noh gained a lot of energy after people started to enjoy it as shikigaku.

Uchida: The unique utai style called tsuyo-gin (strong chanting) is also said to have been established during the Edo period.

Kanze: The innovation of tsuyo-gin was truly great and helped to extend the range of Noh expressions.

Uchida: The foundations were created over a long history and today we can learn utai (chanting) and shimai (short dance performance) as refined techniques.

Kanze: This is all the more reason for me to hope that many people will experience Noh. It is absolutely more enjoyable when performing rather than just watching it. Again, this is the message I would like to give everyone. (End of Part 2)

June 3, 2014

Cooperation: The grand master of the Kanze School

Kiyokazu Kanze (観世清河寿), 26th grand master of the Kanze School

Born in Tokyo in 1959. His father was Sakon (Motomasa) Kanze, the 25th grand master of the Kanze School, whom Kiyokazu succeeded in 1990. He leads today's world of Noh as the 26th grand master of a line going back to Kannami and Zeami in the Muromachi period. He has performed across Japan and in many other countries, including France, India, Thailand, China, the United States, Germany, Poland and Lithuania, in revived plays such as Hakozaki and Akoyanomatsu and new plays such as Rikyu and The Conversion of St. Paul. He has received both the new face and top awards of Japan’s minister of education, culture, sports, science and technology, as well as the Chevalier award from the French government. In Noh, he is the holder of an important intangible cultural property of Japan. He is chairman of the Kanze Bunko Foundation and the Kanze-Kai Association, a councilor of the Japan Arts Council, managing director at the Nihon Nohgaku Association, and managing member of the Japan-China Cultural Exchange Association. His books include Ichigo Shoshin.

Interviewer: Takahiro Uchida (内田高洋), the-Noh.com

Uchida entered the Noh club of the Hosho School at Kyoto University and became captivated by the art there. Since then, watching plays and learning about all aspects of Noh, he has practiced singing and dancing with the Hosho School as well as playing fue (flute) at the Morita School and taiko (stick drum) at the Kadono School. He also writes and edits the Hosho newsletter of the Hosho School.