Interview

Interview

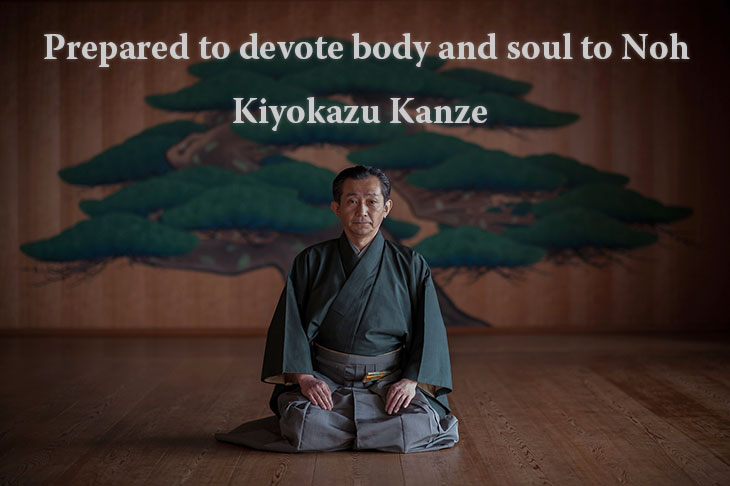

At the end of April 2013, I visited Kanze Noh Theatre in Tokyo's Shibuya Ward to meet Kiyokazu Kanze, the 26th grand master of the Kanze School.

Although the year 2013 marks the 680th and 650th anniversaries of the births of Kannami and Zeami, respectively, Kanze kindly made time in his busy schedule for our interview. I asked him about his plans for the two anniversaries.

Kanze is a man who uses warm and thoughtful language. Relaxed yet smart, he seems to enjoy being himself. His passion when speaking made me think of a phrase I had half-forgotten: ready to sacrifice body and soul. I was moved by his devotion to Noh and to its future. (June 3, 2014)

![]() Part 1: To Pass down Noh over Generations

Part 1: To Pass down Noh over Generations

Interviewer: Takahiro Uchida, the-Noh.com / Photos: Shigeyoshi Ohi

Part 1: To Pass down Noh over Generations

Cultural assets of Kanze family unveiled at exhibition for anniversaries

Uchida: The year 2013 marks the 680th and 650th anniversaries of the respective births of Kannami and Zeami. As the founders of Noh, they are huge figures not only for the Kanze School but also for the entire world of Noh. What are you planning to do to celebrate these anniversaries?

Kanze: As their descendant, it is great honor to be able to celebrate the births of Kannami and Zeami, as this would not have happened if the world of Noh had not survived all of these years. I feel honored and blessed, while offering deep thanks to all of my ancestors.

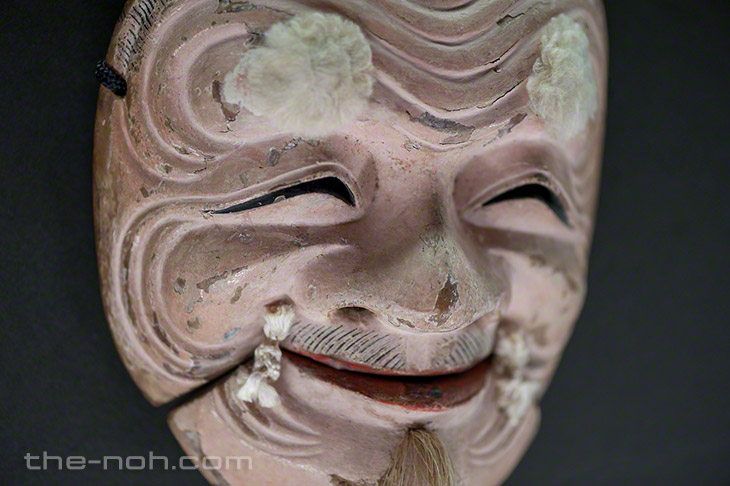

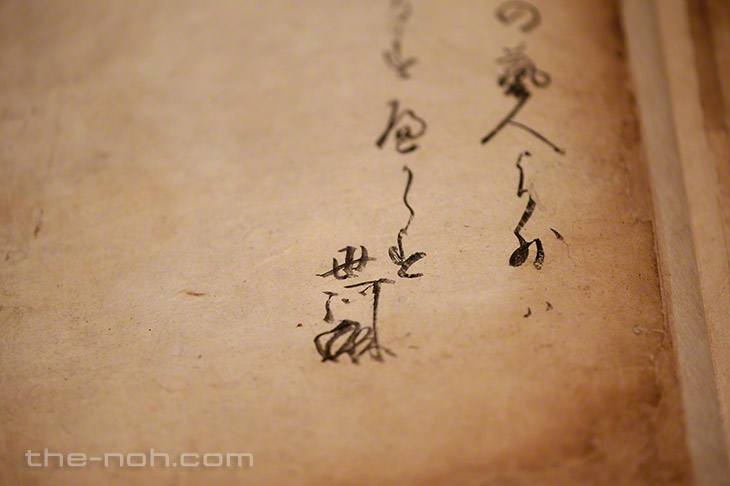

Books written by Zeami himself and Noh masks that are believed to have been worn by Kannami have been passed down within the Kanze family. From time to time, I read these books and wear the masks marked with the perspiration of Kannami. When I put these on, traces of my ancestors' sweat mingle with my own and sometimes go in my mouth. This may sound too dramatic, but when it happens, it feels as though their DNA and mine are coming together across seven centuries. This makes me feel close to my ancestors and inspires feelings of awe for them.

Uchida: I was able to visit a commemorative event to mark the two anniversaries: the Fushi Kaden - Kanze Soke exhibition at Ginza Matsuya department store in Tokyo. At this event, the Kanze family unveiled treasures and cultural assets that have been passed down the generations. It made me feel close to your ancestors beyond time, too, although I can never be as close as you are.

Kanze: As I mentioned in my speech there, the collections have survived wars and disasters, although some documents were burned. Each time I see the collections, I strongly feel the profound thoughts of my ancestors and their arduous efforts. I hoped that as many people as possible would come and see these treasures that have been passed down to this day thanks to their hard work.

After Tokyo, the exhibition moved to Jotenkaku Museum in Kyoto, in the precincts of Shokoku Temple. Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu (1358 - 1408), who had strong relations with Kannami and his son Zeami, established the temple. I was delighted to be able to hold the exhibition at a place with links to this history. The encounter of Yoshimitsu, Kannami and Zeami at Imakumano Shrine in Kyoto led to the Noh of today. The 640th anniversary of this meeting is coming up in 2014.

Mask for Okina called Nikushiki, created by Miroku during the Heian period. The play Okina offers prayers for peace and good harvests. It was performed even before Noh was established.

Fushi Kaden, Volume 6, Kashu, written by Zeami in the middle of the Oei period (1394-1428). This is the only original Fushi Kaden script that has survived until today. It has been passed down only within the Kanze family and is considered a family treasure.

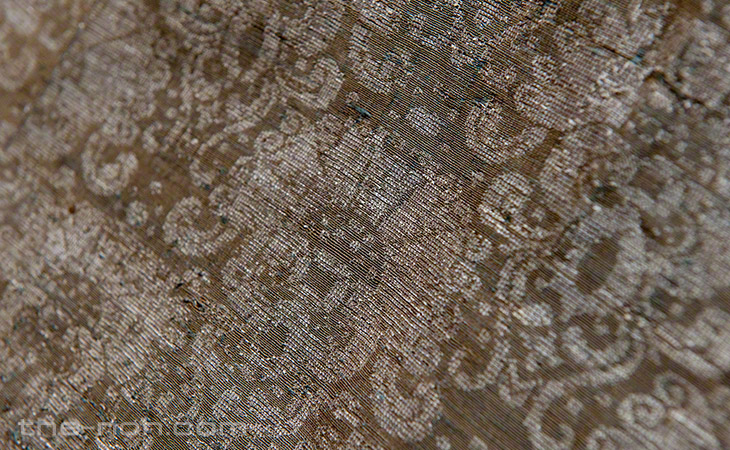

A blue lined kariginu (outer robe for a male character) featuring hexagonal patterns and cranes, presented by Shogun Tokugawa Hidetada. The blue robe with gold brocade forms a set with a lined kariginu with turtle patterns.

Uchida: I would like to ask you to tell us more about the era when Zeami lived and about the Kanze family in the second part of the interview. The exhibition is also due to be held in Nagoya in the fall of 2013.

Kanze: We plan to have the exhibition at Matsuzakaya Museum from Oct. 19 through Nov. 24. Please go along and imagine what it was like to live in the era of Kannami and Zeami.

Uchida: Noh performances and other events are also scheduled.

Kanze: On July 8 and 9, we are due to perform Okina and Hagoromo at Fere Castle in Reims in the Champagne region of France. Also, on July 20, the revived play Akoyanomatsu will be staged in Yamagata, where the story is set. On July 30, Hachinoki and Uto will be performed to support victims of the Great East Japan Earthquake. On Oct. 18, Kanze-Kai will put on Higaki Rambyoshi; while Obasute will be performed at Otsuki Noh theatre on Nov. 16.

Among other unique events, there will be an orientation (entitled "Encouragement of Noh and Traditional Japanese Music”) for the Department of Traditional Japanese Music (Noh major) at Tokyo University of the Arts. On Aug. 8, we are inviting elementary and junior and senior high school students to a free Noh play, which will also bring together performers from other genres such as shakuhachi (Japanese flute), sokyoku (koto music), and nagauta hayashi (song with musical accompaniment). As I have explained on various occasions to parents and older people, children can aspire to become Noh actors even if they are not born into Noh families. I hope this event will give children and their parents a chance to develop an interest in Noh and to think about entering the world of Noh.

A Noh perspective on the origins of Japan

Uchida: Noh has continued for around 700 years. Please explain what you feel in daily life as you work to pass down this long tradition.

Kanze: The other day, I gave a lecture at an event called “Seeking the origins of Japan: For our time in chaos.” This was organized by Mr. Susumu Nakanishi, who is an eminent scholar on Man'yōshū (Japan’s oldest existing collection of poetry). Film director Masahiro Shinoda was also among the people at the event. Let me share what I said there on what I think about on a daily basis. At the start of the event, Mr. Nakanishi told us something very wonderful: The origin of Japan lies in “harmony,” “symbol” and “respect.”

Here, “harmony” indicates thoughtfulness to others, relationships among people, and a way of life based on trust, while “symbol” suggests a system or method of using specific objects to illustrate the ways of the world. In the world of Noh, for instance, this would include the books and original Noh masks that have been passed down in the Kanze family over the generations. Mr. Nakanishi said that the beauty of these masks, in particular, give Noh a strong visual impact that appeals to audiences who are newcomers to this traditional theatrical form, and that there is nothing in the world that can rival them. “Respect,” meanwhile, is a heart of respect for others, which should constitute the basis for being a human. He took as an example the statue of Ninomiya Sontoku (the Edo-period agricultural leader and philosopher) carrying firewood.

After the speech by Mr. Nakanishi, I spoke about the origins of Japan from the perspective of Noh. In Noh, for example, there is a role called the kōken. This may seem like a supporting role, but it is in fact the person who supervises and is responsible for the play through to the end. If the shite (lead actor) falls on the stage, the kōken will take his place for the rest of the play. The role of the kōken is to make sure the performance does not end halfway through. The kōken must be committed and ready to fulfill this role. The reason the kōken is on the stage is probably that Noh plays are for encountering and communicating with gods and praying for the souls of the deceased. If the performance stops in the middle, the communications with the gods and departed human souls are interrupted. It is a sacred rite that has to be carried out to the end. We can see these things in the role of the kōken.

We can also say that there are deep links between the Noh stage and the gods because long ago Noh stages were built facing shrines, dedicating performances to the gods. There are also plays such as Okina that are like rites to pray for world peace and big harvests after a god comes down to the world. Noh also changed dramatically after its encounter with Buddhism, adding breadth and depth to its theatrical significance. Since sarugaku (an early name of Noh) plays were often performed at memorial services called shushoue and shunie, as well as at kanjin events to raise funds for the construction and repair of temples, they became sophisticated and were watched by a wide range of people. By incorporating Buddhist teachings, the content must have also become increasingly profound.

Mask for waka-onna (young woman role), created by Kawachi, the mask creator of the Kanze-za troupe who was known as the top mask maker of the Edo period. It is the last classical Noh mask and is known in the Kanze family as the lonely wakaonna.

A yellow-green Okina kariginu with patterns from China called “shokko”, presented by Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu.

A yellow-green Okina kariginu with patterns from China called “shokko.”

A light-brown Okina kariginu with flower patterns from China and silver brocade, presented by Shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu. It is a valuable robe that is believed to include fabric from overseas.

A light-brown Okina kariginu with flower patterns from China and silver brocade.

Uchida: These aspects also tell us how close Noh has been to the world of gods and to the world of those who have passed on.

Kanze: The structure of fukushiki mugen Noh (dream Noh in two parts), which was created by Zeami, successfully describes the link with the world of ghosts. Those who have departed for the Underworld appear before traveling priests. Through questions with the priests and dance, they leave the world a message: "Please remember that we lived in this world." They then vanish. I assume it is this form of dramatically conveying the strong feelings of the deceased that has allowed Noh to reach the present day while maintaining its vitality. I believe that a heart that prays for the response of departed souls lies at the very origin of our minds and Japanese people's way of expressing kindness. Noh has survived until today because it cherishes the origin of the heart.

Also, Noh is often said to be a type of play that deems a simpler expression to be more beautiful. The Noh stage is simple, with no large set pieces, and the light does not grow brighter or darker during the play. Since the actors wear masks, human facial expressions are designed to play no role. Noh sometimes uses simple and symbolic props, but one fake branch of a cherry tree can represent a whole mountain of cherry trees and only a frame is needed for a boat. By abandoning all figurative materials, we can stimulate people's imaginations and describe purely the world of emotions. By omitting redundant objects and creating blank space, we let the blank space speak for itself. It is the same method used in Japanese painting and tea ceremony. I believe this is the Japanese spirit of beauty.

This way of creating beauty through abbreviation is also seen in Noh movement and dance, which have only limited forms and expressions. An actor expresses grief with a simple movement called shiori, lowering the face slightly downward and covering the eyebrows with the hands. Dances that may look complex are structured with only basic movements, such the kamae standing posture, hakobi steps, and sashikomi to bring a fan in front of the eyes. In kamae, an actor may appear simply to be standing on the stage, but he has energy extended around him and stands firmly with a balanced energy that feels like being pulled tightly from all directions. Noh movements are carefully selected from the movements of all human beings and compressed to the greatest extent.

Uchida: Eliminate, eliminate and eliminate even more. The Noh movements that remain are chosen well.

Kanze: I think that performing a Noh movement on stage is like drawing a kind of an abstract picture rather than a figurative one. The performance has great density, as it has been refined over a history of nearly 700 years. Noh movements are unique and different from regular physical ones. It is hard to put into words, but it is something like an action that uses a microscopic sense deep inside the body, at the cell level perhaps. Our ancestors' spirit of beauty dwells in even the single movement of slightly raising the right hand. By learning these movements through repetition, Noh actors absorb the movement patterns into our minds and bodies to take in a traditional beauty. In other words, these patterns are crystals of Japanese sprit and culture. A beautiful mind automatically arises in a beautiful pattern. This is what I talked about during the event.

In the world of Japanese classics, including Noh, a sense of courtesy is very important. The Kanze family has the principle of not teaching Noh to anyone with bad manners, even if they are children. We have kept this precept for around 700 years, although people today consider it to be nonsense.

In this fast-food era, people can eat anything they want 24 hours a day, while racing against time and living busy days. They don't even remember if they have seen the sun or the moon that day. We have already moved into such an era, but it is not good. Can't we find a way to get back to nature? As the sun rises, we should be aware that it is nature that lets us live and sense that the sun will reach its highest point in the sky and set in the sea in the west. This shouldn't be difficult. Otherwise, I am afraid Japanese civilization will stagnate in the future.

Actors need training that gives a glimpse of hell

Uchida: As a Noh master, what do you think is important for refining Noh techniques?

Kanze: At New Year, I had an opportunity to talk with Kabuki actor Tamasaburo Bando for an article in the Nihon Keizai business daily. During our discussion, we agreed that it is extremely important that lessons must be something that make actors have a glimpse of hell. Tamasaburo said, “A person who is performing an art to entertain others must see hell.” I feel the same and replied, “Actors have to push beyond their limits during training.”

But if we mention “seeing hell,” there is a concern that people may associate this with physical punishment as many have the impression that physical punishment is used in traditional Japanese arts such as sumo and judo. But this is not the case. When teaching traditional performing arts or martial arts, it is absolutely wrong to administer physical punishment. Without any violence at all, we can still train people hard enough to make them catch a glimpse of hell. For this, however, the seriousness of the trainee is extremely important – whether the person is doing the practice in a casual way or is working seriously to test their limits.

At the moment, the voice of my son Saburota is changing, so I am making him focus on learning patterns rather than singing. What I always tell him is to make an all-out effort. He is in the basketball team at school and is exhausted when he comes home after practice. But there are Noh lessons afterward. I tell him I won’t go easy, so he never should either. He may bang his knees when learning the tobikaeri movement, but he must do his best. Also, he should practice singing even if he is sick. I won’t say he has to work until there is blood or vomit, but he shouldn’t ease up. For lessons that test his limits, he can never go easy. That is the lesson that makes an actor have a glimpse of hell.

Lessons that give actors a glimpse of hell also have rewards for the teacher. Teachers shouldn’t take it easy and must always be on their guard. Their children or apprentices will soon understand this. I believe that apprentices are a reflection of ourselves. We know there are some who can’t immediately do what they are told to do, but the responsibility of teachers is to help them get there.

Perform Noh and enjoy it more

Kanze: Let me change the subject. Noh was performed by many warriors of the Sengoku period, including Oda Nobunaga (1534-1582), Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1537-1598), Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616). Why do you think they did this?

Uchida: I suppose there are various reasons.

Kanze: They may have understood the beauty and brilliance of Noh and also sought to educate themselves. By memorizing Noh songs, they could get a taste of Tale of Genji, Tale of the Heike, Kokin Wakashū (Collection of Ancient and Modem Japanese Poetry) and Shin Kokin Wakashū (New Collection of Ancient and Modem Japanese Poetry), without reading them all. For these shoguns, Noh may also have been a cultural device for ruling the nation as Ashikaga Yoshimitsu had done.

First and foremost, though, Noh can be enjoyed to the full when you perform it rather than watch it.

Uchida: I am an unskillful amateur apprentice myself and have learned at firsthand that we can enjoy Noh more and more as we practice it.

Kanze: I imagine so. You can feel a far greater sense of achievement when you perform Noh. Whether you are good or bad, being able to complete one Noh play will give a sense of achievement that you can’t get anywhere else. Noh is most enjoyable when you perform it. If you practice Noh and also watch it, you can enjoy it twice over. I hope that as many people as possible will learn how enjoyable Noh can be.

For amateur actors to enjoy utai (chanting) and shimai (short dance performance), however, the lessons shouldn’t be painful. Amateurs don’t have to cut corners, but I believe there should be a different approach from the one for professionals. For the training of amateurs, I can refer to the methods employed by the previous grand master of the Kanze School (the 25th grand master, Sakon Motomasa Kanze) for a lecture he gave at Tokyo University of the Arts. Initially, when he first taught utai to the students, he made them kneel to sit, but they tended to lose concentration as their legs became numb. As an alternative, the grand master decided to have them sit on chairs. Also, for shimai, he allowed them to wear jerseys instead of montsuki with hakama (kimono trousers), so that they could observe their own physical movements more clearly. Without sticking to the traditional form, he devised effective and innovative methods without hesitation.

Helping people understand the appeal of Noh

Uchida: What are you planning to do to help people appreciate the fun, pleasure, and enjoyment of Noh?

Kanze: There are a number of things I have a strong wish to do. I hope to provide as many people as possible, especially young people, with a chance to be exposed to the essence of the classics by utilizing the space at Noh theatres in unconventional ways.

For instance, one way would be to offer visitors green tea at the entrance to the theatre, with flowers arranged to represent a scene from a Noh play. The three arts – Noh, tea ceremony and flower arrangement – have strong cultural links dating back to the Muromachi period, and I want to get the most out of these. Once the audience is seated, I would like them to enjoy not only Noh but also other classical performing arts, such as Bunraku, Kabuki and Rakugo. For example, a Rakugo stage could have a performance of a story like Funa Benkei, which has close ties with Noh. There should be a stage that makes use of the links between Noh and other performing arts.

In the field of flower arrangement, there are two popular masters I would like to ask for help in turning the entrance of a Noh theatre into a wooded landscape: Akane Teshigawara of the Sogetsu School, a former classmate of mine, and Ami Kudo of the Ohara School.

This is a project I have long discussed with Tamasaburo but have yet to realize. I plan to incorporate some elements into the orientation at Tokyo University of the Arts in August 2013 and use the experience to realize the project by the end of the year. I am eager to unveil this in the near future.

Uchida: How exciting! I hope people will discover that Noh is an art that can be enjoyed casually and also develop an interest in performing it themselves.

Kanze: Kanze: The project is still at the concept phase, but I plan to call for cooperation across the schools to create a stage with a new perspective. I often talk about this with Kazufusa Hosho, the 20th grand master of the Hosho School. Since the Kanze and Hosho schools share the same artistic roots in kamigakari or kyogakari (the remaining three schools come from the shimogakari tradition), we meet frequently and talk about the future of Noh. He has a youthful and flexible perspective, so I hope we can work together, inspire each other to give the world of Noh a boost, and push forward with activities to give lots of people the chance to appreciate Noh.

You can’t get them anywhere else. Kanze Noh theatre goods

We are offering visitors souvenirs available only at Kanze Noh theatre. Get these unique souvenirs for your family and friends, or even yourself.

(Clockwise, from upper left) Disposable chopsticks with gold powder, a ticket holder, a vinyl bag with Kanze School patterns, a box of cookies developed with sweets maker “columbin,” and the “Kanze Soke” (grand master of the Kanze School) candies popular with kids.

Masters beyond any school

Kanze: I love to watch performances by Akiyo Tomoeda of the Kita School. I’ve been a big fan of his since childhood and have often watched him. Whenever I see him perform, it feels as though a pleasant gust of breeze is blowing through the seats. There is the term “style,” but he himself is literally a style of Noh performance. You may say that a wind doesn’t blow in a Noh theatre, but he actually brings in a wind. A gust of refreshing breeze blows as the tension rises. I always hope to be an actor like him. To give an example, in the first half of the play Ukai, the shite is a shabby person who has broken the law against killing to satisfy his desire. Even playing a role like this, Tomoeda retains grace and dignity. I wonder how he does this. He must embody Riken no Ken, the teaching of Zeami that performers have to separate themselves from their bodies and performances and evaluate their techniques objectively. Those who tend to become deeply immersed in a role would not be able to perform like Tomoeda does.

Uchida: As I was listening to you, I remembered that Kennosuke Kondo of the Hosho School says that a shite should not be too entertaining while he is performing.

Kanze: Kennosuke Kondo has a sense of cleanliness. Kennosuke and my father were very close. During the evacuation, he even lived at our home on a temporary basis. He also practiced with my father on the stage that used to be in Tamagawa. My father often said to me, “Kiyokazu, what is great about Kennosuke’s performance is the cleanliness. Noh actors should never let the audience imagine their daily lives.” It seems that this cleanliness is created by a childlike innocence. When I watched Kennosuke perform in Midare as part of a project organized by the kotsuzumi (shoulder drum) player Genjiro Okura, his performance had a childlike innocence and I wasn’t allowed to believe he is over 80. I felt a state of innocence. I want young people at the Kanze School to see such performances, and they must see them. Masters are great beyond any school. I want our students to be exposed to these performances.

In a play organized by the Kanze Bunko Foundation, I saw Akira Takahashi of the Hosho School play Yōkihi (Yang Guifei). He has a true softness. I was impressed to find him so soft, but I start to feel sad when I am exposed to this softness of his. It is no longer clear whether it is Akira Takahashi or Yang Guifei herself who is standing on the stage.

Uchida: When you watch masters from other schools, is there anything you take from their techniques for your own performances?

Kanze: I admire them. At the same time, I am really curious about how they sing and dance.

In terms of the school, I admire Gensho Umewaka. I am pleased to say that I have performed all five rojo plays, Sekiderakomachi, Higaki, Obasute, Oumukomachi and Sotobakomachi, and it was really great that Gensho sang in all of them. Without him, I would not have been able to complete the five. He excels in various aspects. It may sound a little strange, but it seems as though he has a perfect pitch within him. What I mean is that he is so great and accurate at staying in tune. He must have five keen senses. You will probably find few from any of the five Noh schools who can sing with such melody and deep feeling. I feel honored to live in the same era and to stand on the same stage as him. (End of Part 1) ![]()

Cooperation: The grand master of the Kanze School

Kiyokazu Kanze (観世清河寿), 26th grand master of the Kanze School

Born in Tokyo in 1959. His father was Sakon (Motomasa) Kanze, the 25th grand master of the Kanze School, whom Kiyokazu succeeded in 1990. He leads today's world of Noh as the 26th grand master of a line going back to Kannami and Zeami in the Muromachi period. He has performed across Japan and in many other countries, including France, India, Thailand, China, the United States, Germany, Poland and Lithuania, in revived plays such as Hakozaki and Akoyanomatsu and new plays such as Rikyu and The Conversion of St. Paul. He has received both the new face and top awards of Japan’s minister of education, culture, sports, science and technology, as well as the Chevalier award from the French government. In Noh, he is the holder of an important intangible cultural property of Japan. He is chairman of the Kanze Bunko Foundation and the Kanze-Kai Association, a councilor of the Japan Arts Council, managing director at the Nihon Nohgaku Association, and managing member of the Japan-China Cultural Exchange Association. His books include Ichigo Shoshin.

Interviewer: Takahiro Uchida (内田高洋), the-Noh.com

Uchida entered the Noh club of the Hosho School at Kyoto University and became captivated by the art there. Since then, watching plays and learning about all aspects of Noh, he has practiced singing and dancing with the Hosho School as well as playing fue (flute) at the Morita School and taiko (stick drum) at the Kadono School. He also writes and edits the Hosho newsletter of the Hosho School.