|

|

|

| | Home | People behind the Scenes | Koichi Takatsu |

| |

|

|

|

| Photos: Toshiro Morita |

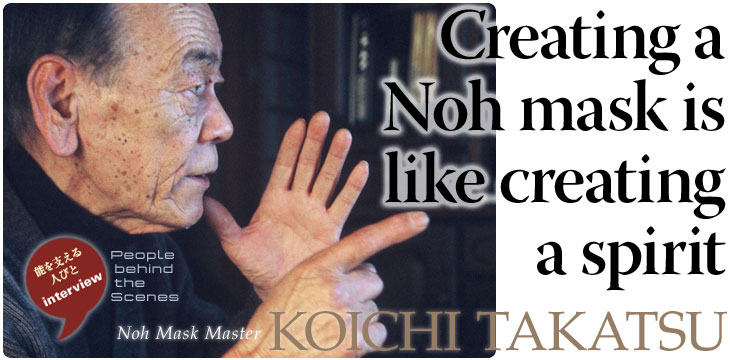

At times they give us a sad expression, and at times they give us a joyful expression. They are full of different emotions and thoughts, these mysterious Noh masks. The workshop where these masks are made is in the Izu peninsula, in the mountains overlooking the ocean. This is the workshop of Koichi Takatsu, The Noh Mask Master. Takatsu has no teacher himself, learning the craft of Noh mask making through self-study and becoming one of the top mask makers of his generation, earning the praise of many Noh masters and having his masks appear on stage every day. Takatsu told us about his struggles and inspirations while learning the craft, and the profound feelings he has for Noh and its masks.

![]() Part 1, Learning the Craft

Part 1, Learning the Craft

![]() Part 2, Feelings About Noh Masks

Part 2, Feelings About Noh Masks

![]() Part 3, In the Workshop

Part 3, In the Workshop

Part 1, Learning the Craft

The Path of Learning Noh Mask Making

Life Changed When I First Encountered Noh Masks

|

Photo: Toshiro Morita |

-- (Editing Department) We began by asking Takatsu how he first became involved in the world of Noh mask making.

Takatsu: Whenever I look at an object, I always feel that my life path changes in some way.

I used to love paintings. I practiced art in after-school activity of middle and high schools, and found oil painting extremely interesting and thought that was the path I would pursue. In the first half of the Showa era, I lived in Hiratsuka. The art teacher happened to be from Kyoto, and I visited his house in Kyoto for a week during summer vacation with other students. He gave us a tour of places with Japanese art, giving us the opportunity to study. On the last day, he told us he had something interesting to show us and took us to his relatives’ long-established store selling Uji tea. There he showed us a Noh mask, and I was extremely impressed.

-- Was that the first time you had seen one?

Takatsu: Yes. It was a woman’s mask, but at the time I had absolutely no knowledge and knew nothing about it. About all I knew was that I had seen it once in a book. When I actually laid eyes on it, I was fascinated by what it was and couldn’t forget it.

-- What drew you to it?

Takatsu: I can’t really express it in words. I was just fascinated by what it was. Around eight of us went, but only two of us were interested in the mask. I think what might have interested me about it was that I was always interested in sculpture and ceramics since I was young. Some people might not have thought much about it, but I happened to have an amazing first encounter, and my interest continues to this day.

I left home and began self-study still unsure of myself

-- Tell us about what was happening when you first entered this world.

Takatsu: I wanted to follow this path at around the time I graduated from high school, but because of the times, no one supported me. My friends, parents and the people around me understood painting, but I felt like they thought I was crazy for deciding to pursue the somewhat different world of Noh. But after thinking about it for years, I decided to leave home. There were no opportunities with Noh masks in the Kanto area, so I saved up money working a part-time job and asked for help from the tea shop owner of my school teacher’s relatives in Kyoto.

-- Did you learn from a master in Kyoto?

Takatsu: The situation was totally different from now, where it was quite difficult for someone with no experience to just become a disciple of a Noh mask maker. There was no way for me to start learning mask making. But I learned the most from looking at masks, and the most opportunities to do so was around Kyoto and Kansai. I looked at famous pieces and repeatedly tried to recreate them myself. Now we use paper stencils, but at that time we couldn’t have imagined them.

I started by using chisels to make them, but they always came out larger than the measurements. There was no one to tell me standard size. I continued to support myself through my part-time job and continued my process of trial and error.

Feeling overwhelmed as I began to study

|

Photo: Toshiro Morita |

-- So you began to teach yourself by imitating others?

Takatsu: Everyone knows Noh masks are carved out of wood. But it’s hard to know how to apply color. At first I had no idea what nikawa (animal glue) was, so I started learning about it. After I learned about nikawa, I still had no idea about gofun (pigment), so I started studying it.

-- It seems like looking at a huge dictionary one page at a time.

Takatsu: You have to experience it. I understood that nikawa was an adhesive, and that it was mixed with gofun to paint color, but I didn’t even know how much water to dilute each one with. You start by diluting the hard nikawa, thinking the harder the better because it is an adhesive, but you end up with something like starch syrup, which doesn’t work.

No matter how many times I applied the nikawa it didn’t come out right, and the expression of the face wouldn’t be right or the skin would come out harder. I wondered how the old masks came out so clean looking. I knew I had to go through a process of trial and error with the proportions. Completing a mask seemed so far away, and I had to start by learning the basics of the basics.

The daily struggle was a long road, but the right track

-- More “getting used to” than “studying”. Truly learning through experience.

Takatsu: The day-to-day learning process was difficult. Now I teach Noh mask making in seminars. There, people feel that they will be able to make masks if they just master the skills. But just learning the basics doesn’t mean you will immediately be able to make a Noh mask. Techniques established over many years cannot be learned overnight. For example, there are detailed parts of the process that the lathe worker understands by feel only. That is an amazing thing that can only be learned through years of experience. The skills are not something you can pick up in just a day. Lots of experience and the ability to sense subtle differences are incredibly important, and difficult.

I didn’t have a teacher, and so it took me a long time to get there, but I feel like because of that I built up an incredible amount of experience within myself. A very formidable experience I wouldn’t have gotten had I just followed orders from a superior. I felt like I was battling with my creations every day.

Even one petal of a Buddhist statue was a task and training

-- Please tell us a story from when you were struggling to learn mask making.

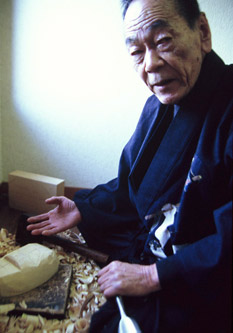

Takatsu: Leaving home to study mask making, there were lots of desperate and frustrating times. Even though many people had pursued mask making as well, most of them gave up because they couldn’t make enough money to eat. I was young and alone and worked like mad, and if I had a family I’m sure it would have been impossible. I still had to work a part-time job to make ends meet, but that helped in my work study also, as I chose a job that involved glue. There were many Buddhist statue sculptures in Kyoto, and I worked at one of their shops. It was about how much I could earn by making one vase or one lotus petal. I was able to keep the wood scraps, which were mostly nice Japanese cypress (hinoki) scraps. At the time I could not even to buy materials, so I was quite grateful. Every night it was a battle with the wood chips.

I used to use cedar for practice, which is not really suitable for Noh masks, but cheaper than cypress. I think it was a good way to get the sense of carving.

Only creating masks used on stage really matters

-- How long did this process take until you started to understand Noh masks?

Takatsu: Even after I thought I understood it in my mind, it took quite some time to develop a deep understanding. Carving Noh masks does not just mean looking at the mask. You have to study the stories of Noh and the on-stage performance. Noh masks are meaningless if not used on stage. Since they are tools used in the performance of Noh, you can’t understand them by simply making them. Going to a theater and watching a Noh performance is extremely important.

I used to go to the Kongoh Noh Theater often. The audience was usually small then, but those that did attend had a great eye for the performance. Since Noh performers (masters) were playing before that kind of sophisticated audience, they put together amazing performances. Having such an astute audience watch their already refined performance led to a sense of pressure and a high level of performance. I wanted to know what Noh masks used in that level of performance were like.

Also from the kind of town Kyoto was and its history, I did my best to take every opportunity to see how antiques reflected in Noh masks.

-- You said that looking at Noh masks was the foundation of your study.

Takatsu: This was when Noh masks were kept among collectors. For example, when I went to an antiques shop in Uji, I happened upon an excellent mask shown on display. I remember looking at them through the glass. More than ten years of study passed like nothing with a lighting speed.

Meeting people broadens your world

-- Was there a specific turning point when you established yourself as a Noh mask maker?

Takatsu: This was of course through meeting someone. I gained experience from everyone who showed me Noh masks, starting with the owner of the tea shop in Uji. I gradually began to have more and more Noh masters using my masks and supporting me. I preferred to have Noh masters look at the masks I had made and consider using them rather than making masks based on orders. Through this process I built connections and met more people through them. I developed my network in this way, and it is a style that I keep even until today.

I got to know the Kongoh family in Kyoto, who later invited me to see a collection of Noh museum in Tanba-Sasayama, where I was able to further polish my skills.

Growing as a Noh mask maker through restoring masks

|

Photo: Toshiro Morita |

-- What kind of things were you involved with at the Noh museum?

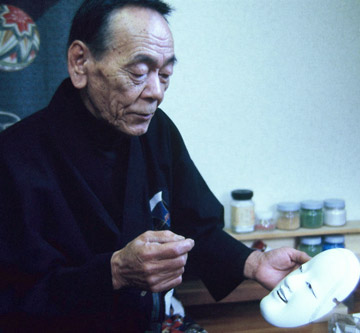

Takatsu: The Noh museum is a wonderful facility, and over the years they have built an amazing collection of Noh masks. I didn’t just visit, but went regularly as a researcher and focused on studying Noh masks. I restored many Noh masks there, and continue to do so still now.

The skill of mask restoration is essential to a Noh Mask maker. If you have the skills, you are able to have more chances to look at good masks, which is helpful for future. You start to understand what a good mask looks like after spending days and days to look at the expressions of the amazing masks that come in to be restored. This job carries a lot of responsibility, as there is serious consequence if the masks are damages. Those trial and error approaches due to no teachers was unexpectedly useful for the task of restoration. Doing so, I began to see things others didn’t.

-- What, for example?

Takatsu: How to distinguish colors. In painting layers of colors, you begin to know what kind of color is below another. You can’t tell this by just being taught. You have to fail at painting numerous times to polish your skills. In this process you start to see many things. Failure ends up helping restoration.

The scariest part of restoration is creating bags under the eyes of the masks. The skin of the masks has aged for hundreds of years. Applying new material to the surface makes the new nikawa pull against the old skin, and if this continues, wrinkles can develop on the face of the mask. This is why using nikawa in such a delicate process.

Making Noh masks every day

-- When did you eventually move to the workshop?

Takatsu: I came home to Hiratsuka when I was 45. I worked at and around my home, but I couldn’t really focus on work being in the city. I looked for a good place to work, and was introduced to this place by meeting someone. This is a quiet and secluded place where I could work even in the middle of the night. Once I start working, I get really into it and time stops mattering.

-- How is your business?

Takatsu: In Kanto, thanks to the help of Motoaki Kanze, work has been almost steady. I have been working on teaching Noh mask making at public seminars. But these jobs don’t really make much money. Honestly, I wonder if I will be able to keep doing it. With fine arts or other crafts, if you work hard you achieve some level of status, but Noh masks are at best tools. They don’t sell for high prices. But lately I do hear about people selling masks at arbitrarily high prices online and people who don’t know what they’re doing buy them. I don’t know whether those masks are actually used.

If masks become too expensive, young Noh performers won’t buy and will only borrow them. I’m not saying that’s bad, but the level to which the art can be pursued is limited with borrowed masks. The art becomes deeper when the Noh masks are used and used as an important tool by the same hands. Having more people collect masks that are actually used while making more money would be ideal. ![]()

| Terms of Use | Contact Us | Link to us |

Copyright©

2026

the-NOH.com All right reserved.