|

|

|

| | Home | People behind the Scenes | Unosuke Miyamoto |

| |

|

|

|

|

Photo: Shigeyoshi Ohi |

Miyamoto Unosuke Co., Ltd., located in Asakusa, Tokyo, is a shop specializing in taiko, mikoshi and other objects and instruments used in festivals. In additions to producing and selling kotsuzumi, ōtsuzumi and taiko used in Nohgaku, the shop supplies the instruments used by the Imperial Household for the performance of gagaku, traditional Japanese court music, as well as the mikoshi, or miniature movable Shinto shrines, used in the Asakusa Sanja Festival.

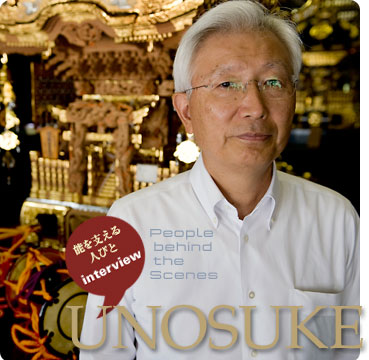

This summer, we spoke with seventh-generation president Miyamoto Unosuke, himself a student of Nohgaku, about the meaning of passing on the craft and his involvement with Nohgaku.

The founding principle of Miyamoto Unosuke Co., Ltd. is “Value Principles,” in other words, doing things as they were originally intended to be done. Communicating this philosophy is the proper way of passing on the craft. This sounds particularly meaningful in the elegant words of Mr. Miyamoto, who seems to embody this very philosophy.

|

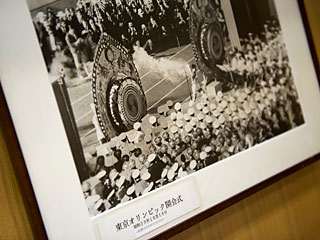

Huge kaen-daiko drums added color to the opening ceremony of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. The picture is part of a display of historic photos in a corner of the main shop of Miyamoto Unosuke Shoten. (Photo: Shigeyoshi Ohi) |

Beginnings as an Edo-Era Taiko Shop in Tsuchiura

Miyamoto Unosuke Co., Ltd. was established in 1861 (the first year of Bunkyū), nearly 150 years ago. The head of the family seven generations before me opened a taiko shop in what is now Tsuchiura, Ibaraki. While the shop originally handled saddles and harnesses, on advice that Asakusa would be more suited to a taiko shop given its large population and demand, my great-grandfather Unosuke moved to Tokyo in 1893 (Meiji 26) and opened a shop there. It is said that he came to Tokyo from Tsuchiura by boat on the Tone River, a nostalgic thought indeed.

Nohgaku Percussion Instruments’ Birth in the Meiji Era

While the old catalogues were lost in a fire and we are unsure of the precise details, we believe that the shop began supplying taiko for use in Nohgaku in the latter half of the Meiji era. We know this from the stamps of the shop on the underside of the skins of older kotsuzumi and ōtsuzumi.

From that point on we began supplying all types of instruments to the teachers of Nohgaku, and have supported and supplied instruments for the training of hayashikata at the National Noh Theatre since our founding.

Supplying Gagaku Instruments to the Imperial Household

In 1926 (Taisho 15), we produced a set of instruments for the funeral of the Taisho Emperor, after which point we began receiving orders from the Imperial Household.

We also provided a large kaen-daiko for the opening ceremony of the Tokyo Olympics. This was a particularly bold move by my father, who received almost nothing in return. The drum was eight metres tall, and eventually ended up just taking up space in our warehouse. But in the last twenty years, the drum has seen much more use, being lent to the Imperial Household for touring performances and used several times each year. I can’t imagine what has made the drum see so much luck, except the effort my father place into making it.

|

Small kotsuzumi drums are sold, but there are also requests for repairs and adjustments. (Photo: Shigeyoshi Ohi) |

The Highpoint of Nohgaku Instruments: The Genroku Era

Nohgaku instruments reached their peak in the middle of the Edo era, during the Genroku era. Nohgakushi of the era were hired by the Shogunate and the feudal lords, together with drum makers. The mindset of the era allowed the craftsmen to focus completely on the creation of the highest quality instruments. With the support of those in power and unlimited funding and time, they were able to produce true masterpieces. While we can approach this level of craftsmanship, we will never be able to duplicate it.

I believe this is true of not only Japanese instruments, but classical instruments such as the violin. We are living in a different age now than when instruments such as the Stradivarius violins were produced.

We create reproductions of instruments of the time and study their construction to attempt to recreate their form, but it is difficult to exceed their quality. While we approach our craft with the utmost care and attention, as the ancient craftsmen were commissioned directly by the feudal lords and could face banishment or hara-kiri for failure, they literally placed their lives into their craft. This is somewhat different from today.

We are also challenged by the fact that quality materials are getting harder to find. This is true for many of the objects used in Nohgaku and is a problem for the entire Nohgaku community.

|

|

One part of the drum-making process. After animal hide from foals, horses or cows is glued to iron hoops and then stitched, it is dried in natural sunlight. (Photo: Shigeyoshi Ohi) |

The Ever-Interesting and Profound World of Instrument Making

Taking the kotsuzumi as an example, the shape of the shell has numerous characteristics and is quite profound. For example, the planing lines on the mortar-shaped shell of the drum differ greatly based on the individual craftsman, so much so that all the individual styles can not be identified. The lacquer work on the front face of the shell is filled with amazing designs, both on the kotsuzumi and ōtsuzumi. The pursuit of quality craftsmanship is truly worthwhile, and we desire to continue to endeavour to produce the highest quality instruments possible.

Our Position as a Supporter of Nohgaku

Having studied utai first under Shinjiro Ban and then under Shintaro Ban of the Kanze School, I am well aware of the wonder of Noh. Unfortunately, I feel that that Noh is losing some of its appeal, with the once-popular Takigi Noh¬ faltering and the number of people practicing Noh decreasing. This is beginning to affect our business.

Noh has 600 years of history, captivating audiences through a combination of its ephemeral and ritualistic beauty and music. Noh is even beginning to be understood by foreign audiences, and has been designated as an example of the world’s intangible cultural heritage. While its status as a traditional art and musical form of Japan remains unchanged, many people feel that something must be done to prevent the tradition of Noh from being lost.

Creating more awareness about the art form should help reinvigorate the world of Noh, and the increased interest of young people is essential. There are many people who do not understand Noh and some who have never seen a Noh performance. I feel this is truly unfortunate.

The Importance of Explaining Noh Abroad

We first need to make sure that everyone has at least heard of and seen Noh. I feel that as more and more people leave Japan to go abroad, they must have at least some understanding of traditional Japanese arts such as Noh, Kabuki and Bunraku (traditional Japanese puppet theatre). There are plenty of foreigners who have seen Noh and are interested enough to study it. It is just too embarrassing not to be able to respond to foreigners who are interested in learning about traditional Japanese culture.

Wadaiko performances are becoming extremely popular among ethnic Japanese communities, particularly in the US. These communities are also quite active in sharing Ikebana and the Japanese tea ceremony. Although their opportunities are limited, these people take great pride in their own roots and cultural identity. While Japan is perfectly suited to cultivating this same sense of pride, I feel that it is being lost. The Japanese cultural roots that were strong during the Meiji era are beginning to weaken.

It is my hope that knowledge and understanding of Noh increase, as it is such a wonderful art form. I feel that Noh is even more refined than Western opera, and wish that Japanese going abroad will be able to share its beauty with the world.

Preparing to Continue the Family Business as the Eldest Son

Being born as the eldest son of a longstanding business, I was prepared from a young age to take over the responsibilities of the shop. I worked in the shop from high school and helped during performances, being brought up under the strict tutelage of many skilled craftsmen of Noh. I saw and understood the difficult nature of the job and worked hard at it every day. There was nothing else that really caught my interest, which in the end I believe was a good thing.

The Unchanged Craftsmen of Noh

We have around twenty craftsmen that produce our taiko and mikoshi. While people point to a decrease in these kind of traditional artisans, fortunately we have not seen a decrease at our shop. We have a good employment cycle with new, younger craftsmen regularly joining our shop. I sometimes wonder why they want to join our business, as the work is neither clean nor easy. I think it is appealing because of the pride we take in our craft that makes the job so worthwhile.

While we have many young people who want to join our shop, only a few are hired. This is because we only take on those who have clear goals in joining the business.

Passing on the Craft is a Matter of Heart

The founding principle of Miyamoto Unosuke Co., Ltd. is “Value Principles,” in other words, doing things as they were originally intended to be done. The “Miyamoto Tradition” is a part of the <i>mikoshi</i> we provide to the Asakusa Sanja Festival. This motto and its spirit is something I communicate to our craftsmen everyday, and while difficult, it is absolutely essential.

In addition to making the objects and instruments used in festivals, we are also involved in supporting religious ceremonies, as Noh posses a religious element. As such, the proper frame of mind and a serious attitude are required to create the instruments of Noh. While the craftsmen can have a hard time understanding this at first, I believe that a feeling of responsibility for passing on the craft gradually develops as the job becomes more and more a part of them each day. It can take years for them to make a real living at this job. While they may acquire the necessary skills after ten years, this is only the beginning. True mastery of the craft requires spiritual development, experience and years of dedication. It is truly a lifetime commitment.

|

|

Inside the drum museum about five minutes by car from the main shop of Miyamoto Unosuke Shōten. Here you can see drums from all over the world and the Miyamoto family collection. (Photo: Shigeyoshi Ohi) |

Generously Supporting the Teachers of Nohgaku

I do not have a special relationship with the teachers of Nohgaku just because I am also a student. They are both important clients and key advisors in producing quality products. To be able create instruments they can look forward to and trust, I feel I must continue to support the performance of Noh.

Consider this story. The head of the Okura School for kotsuzumikata, Genjiro Okura, decided to study and try to reconstruct an old form of Noh and kotsuzumi from Ishigaki Island in Okinawa. I accompanied him on research and speaking trips to the island and then helped him create local awareness and reconstruct the changed kotsuzumi. I have also travelled with my instructor Shintaro Ban to centres of Nohgaku to broaden understanding of the world of Noh.

Sharing the Joy of Instruments

The kotsuzumi produces four sounds, “po,” “pu,” “ta,” and “chi,” which are varied to produce a range of delicate sounds. Even the ōtsuzumi, which is beaten by hand, is able to create quite subtle sounds. The taiko creates a clear sound when beaten with a drumstick. Each drum thus has its own appeal. I want all different kinds of people to visit a Noh theatre, see a performance and become familiar with Noh, and enjoy the music of the hayashi.

The Reasons for the Founding of the Drum Museum and Miyamoto Studio

The Drum Museum, which houses a collection of drums from around the world, opened in 1988 (Showa 63), and the Miyamoto Studio, a practice studio for drums and other instruments, opened in 1993 (Heisei 5).

The Drum Museum boasts a collection of more than 800 drums from around the world with 200 pieces regularly rotated. Miyamoto Studio was created to provide a place for musicians to practice playing the drum as loudly as they like, and is also used as a wadaiko classroom. Both the Drum Museum and Miyamoto Studio were born out of everyday activities and not any specific inspiration, and while not directly related to Nohgaku, we feel they are important in broadening musical awareness.

(September 2008)

Profile

Born in 1941 in Asakusa, Tokyo, Unosuke Miyamoto joined the family business, Miyamoto Unosuke Co., Ltd., in 1965 after graduating from the Meiji University School of Commerce in the previous year. After being named President in 1975, in 1985 he opened the Drum Museum to exhibit drums form around the world. In 1993, Miyamoto established Miyamoto Studio as a practice and instructional facility for traditional Japanese music and instruments including the wadaiko. 2003 marked his succession as the seventh Unosuke Miyamoto.

Miyamoto Unosuke Co., Ltd. website (Japanese)

| Terms of Use | Contact Us | Link to us |

Copyright©

2026

the-NOH.com All right reserved.