|

|

|

| | Home | People behind the Scenes | Nozomu Hayashi |

| |

|

|

|

Photo : SHIGEYOSHI OHI |

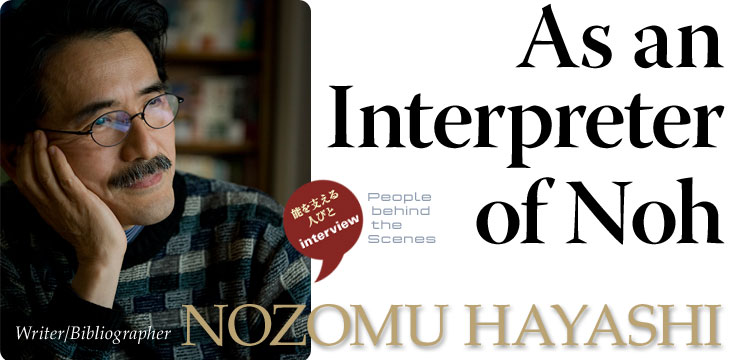

We interviewd Mr. Nozomu Hayashi on an early spring day. No lengthy explanation is necessary and let it suffice to say that Mr. Hayashi is well-known as a man of varied accomplishments. He has deep insight into Noh based on actual experience. Here, in a series of writings, he conveys to us his fascination with Noh and explains the theatre's aspects in a way fully accessible to the layman.

This time, two of our editorial team members, one with some knowledge of Noh and one a total stranger to Noh, visited Hayashi to ask him to select from among his vast knowledge some Noh-related matters to speak on.

Hayashi, quite the dandy, welcomed us with the fresh feeling of spring about him and entertained us by speaking at length in his magnificent voice about Noh.

It should have been a means of studying early-modern literature...

Editor (M) : First, tell us how you first encountered Noh.

Hayashi : I was originally studying Japanese early-modern literature. The Edo period was the golden age of Yokyoku (Noh chants). Yokyoku, was popular outside of the Noh theatre as well, much like pop music today, or karaoke. There were instructors called "Utautai," or singers, who specialized in Yokyoku. They taught certain laypeople of leisure, including merchants and samurai, who learned and memorized Yokyoku. Without some knowledge of the basics of Noh and Yokyoku, it is impossible to study the literature of the Edo Period. For example, even if you have no problem reading the works of Saikaku Ihara, you may not be able to recognize the parody of the Yokyoku "Atsumori.' At the time I was studying Yokyoku there were no reference books on it. I figured that the only way to learn about Yokyoku was to learn it myself.

Editor (F) : Then, as you mention in your book, you met someone very important.

Hayashi : Though I had no connection to him whatsoever before then, I happened to move to right in front of the home and practice room of Reijiro Tsumura, a Noh performer in the Kanze style. When I ran into him on the street, I thought that the time had surely come to learn Yokyoku and Noh. I asked him to make me a trainee. He kindly accepted my request and told me to come around the very next day. That was more than 30 years ago. After that, I became deeply involved in Noh, and joined in the chorus singing utai every chance I got. Mr. Tsumura at times gave public performances while performing for me as a tsure. I spent much of my time in Noh theatres as a supervisor or maku-koken and also working backstage as a dresser.

|

Photo : SHIGEYOSHI OHI |

Editor (M) : So you were almost semi-professional.

Hayashi : That’s true. Also, I enjoyed being trained like a Noh performer in such things as property making and the treatment of masks. I also learned a higher level of skills, including those handed down secretly and only by orally.

It was a much deeper involvement than learning Yokyoku as a simple enrichment lesson. My practice sessions included chants, dance pieces, playing the small hand-drum and the flute. I had a plenty of time for practicing because I was an academic and spent much of my time at home. I often got complaints from the neighbors to keep the noise down. When I would practice the drum, I'd yell out, "Yooh, Hoo!!" and the sound would vibrate the place. I got a lot of complaints. (laughs).

Feeling good as singing an operatic aria

Editor (M) : What made you become involved so deeply in Noh?

Hayashi : The same can be said for an opera too, we feel wonderful when we hear a highly trained voice. Something reverberates deep within. When we hear the e magnificent voice of the late Shinjiro Saka or Rokuro Umewaka, it doesn’t matter whether or not they are wearing masks, does it? Their voices resonate with the entire room. When they sing the rhyming utai, you have the same wonderful feeling you have when you're listening to an operatic aria. After all, though you may not be able to understand the foreign lyrics of opera, utai is sung in Japanese. I am a scholar of Japanese literature and able to understand classical Japanese. It is also true that being involved with the performers and their work, rather than just listening, makes it far more enjoyable.

Editor (M) : What are your favorite songs, or the ones that make you feel good singing?

Hayashi : Every song has its own appeal. Among others, I find a lot of fine songs in the works of Zeami. What are my favorites…? It is quite hard to choose. If I must choose, I would say “Kiyotsune,” “Tsunemasa” and other Heike pieces that invite our compassion would be candidates. “Sumidagawa” is also fine, and “Kosodesoga” is not bad. I like “Tomoe,” too. The subtle and profound sanban me mono such as “Tohoku” and “Hagoromo” make me feel good singing. What makes me feel the best when singing on stage is Shuranori. I really love tunes such as “Tamura,” and find celebratory pieces like “Ishibashi” very good as well.

Editor (F) : What are some other aspectgs of Noh that appeal to you?

Hayashi : The length of a typical Noh play is around 90 minutes, which is short compared to other traditional Japanese performing arts. One of the good things about Noh is that a play conveys a single message, and that message is conveyed in two hours at most when you watch and listen with concentration. Another attraction of Noh is that it has something that is universally understandable even for non-Japanese audiences. While of course there is the language barrier, every action is integrated and essential.

I think these symbolic actions are very universal and common to the Greek classical theatre. This may be the reason why Noh struck a chord with W.B. Yeats, Benjamin Britain and other Westerners. In that sense, Noh may be considered quite modern though it is a classic performing art. It could be said to be attractive to today’s young generation, even they may only be able to understand less than half of an entire play.

Grow accustomed to it first. Then you will find it interesting.

Editor (F) : Like today’s younger generation and non-Japanese, I knew nothing at all about Noh. With my first experiences with it, I would get always get sleepy watching it. But watching "Arna" recently, I was drawn into it and so impressed that I started to cry. It was quite different from falling asleep.

|

“Korenara Wakaru Noh-no Omoshirosa (Finding the Fun of Noh)” A Noh book by Nozomu Hayashi in which Yokyoku is introduced to the layman with an in-depth reading of the lyrics. |

Hayashi : Noh is admittedly overly stylized. Though some performers like Kyuma Hashioka ventured to perform in a different style, the typical play has a very heavy and slow feel to it. Noh was originally the ceremonial music of samurai families. So, it is natural that one would get bored. You need to get used to a whole different pace, a different speed with which time flows.

Editor (F) : In addition to getting use to it, I feel the need to study.

Hayashi : Studying is absolutely necessary. Everything is integrated into words. For example, where someone is traveling in a piece, the scenery along the road will only described verbally. So, nothing can be communicated without understanding the lyrics. Your imagination will be tested. As this is critical, the audience also needs to concentrate. One should strive to activate one’s mind while watching a Noh play. Being able to watch “Ama” without getting bored, as you said, means you have grown accustomed to it. It indicates you were able to understand the message being delivered.

It's not always true that a person who has learned Yokyoku as a performing art will understand Noh. Learning Yokyoku can help you or hurt you; it may be possible that you will be simply singing without understanding the meaning very well. In my case, I started to study Noh by reading the texts, so I was able to fully understand the meaning of every word. It made me realize that such beautiful prose is a very rare thing.

Editor (M) : I had the very same impression. Each and every word is packed with meaning.

Hayashi : Everything is condensed with some ambiguity and no excess of words. One single word expresses much. This is particularly true with the works of Zeami, including “Kinuta” and “Yorimasa.” Even in a violent shura mono (stories of Aceldama), the protagonist plays a deeply nostalgic scene is in the introductory play. Imagining such a scene makes me realize what a beautiful country Japan is. Such a scene simply cannot be communicated to non-Japanese audiences through words. But it is possible for Japanese to imagine the scenery of, for example, Omi-Hakkei, with the snow falling or the moon shining. While watching Noh plays, we Japanese have a enormous advantage to be able to envision the beautiful landscapes and humanity of Japan without needing any explanation. There are many things in Noh that are only comprehensible to Japanese. I think it would be a great pity to reject Noh by saying “I can't understand it.”

Editor (F) : I thought watching a Noh play as a beginner would be the same for Japanese as it was for non-Japanese. But, not according to what you say. I was quite encouraged.

Hayashi : Another point to mention is that Japanese tend to view things as transient and empty. The idea of transience or that everything must pass is a common understanding among Japanese. That is why the beauty of ruination such as is expressed in a story of a battle touches us deeply. We also can perceive time with a single word expressing the passage of a great deal of time. Such may be hard for a non-Japanese audience to understand, including the idea of putting aside a grudge by saying it was something that happened a long time ago.

Editor (M) : While it is not easy to convey the art of Noh to foreigners, our Web site intends to communicate the appeal of Noh to a wide range of people, including non-Japanese people and those totally new to the art. Is there any advice you would like to give those experiencing Noh for the first time?

Hayashi : What you need to do to watch a Noh play is to visit a Noh theatre. You can only appreciate Noh in a Noh theatre, where you share the space with the performers and can feel the vibrations of their voices. Watching a Noh play on television, for example, is no fun. Watching it on a TV screen or as a DVD may have meaning for a practitioner of Noh, insofar as he can compare styles, but the fun of Noh can never fully be conveyed through screen images. At best, less than half of Noh’s enjoyment can be conveyed thus. It’s true for an opera as well isn’t it? It’s no fun watching an opera on TV. The only way to enjoy it would be to watch it live at an opera house. The same applies to Noh, the Japanese equivalent of opera. It is fantastic to send vibrations directly through the audience using no microphone. I really recommend watching Noh live at theatres. The National Noh Theatre puts on promotional performances, but you can also watch Noh performances at events sponsored by a Noh society at a cost of as little as 3,000 yen. You may also enjoy it for free on occasion such as at a study session performed by younger players (editorial note: e.g., Seiunkai of Hojo style). So, why not visit a Noh theatre?

His mission: Convey the fun with words that make sense.

Editor (M) : You are working hard to promote Noh through your writings and commentaries at public performances. What is your overall aim?

|

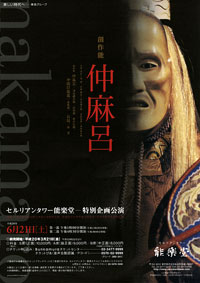

The original Noh play “Nakamaro” written and directed by Nozomu Hayashi will be performed at Cerulean Tower Noh Theatre in Shibuya on June 21, 2008. |

Hayashi : I consider myself an interpreter of Noh. The world of Noh is quite removed from the ordinary person. I neither had a chance to see a Noh play before I was an adult. Tickets are expensive, and there is little information regarding when and where a play will be performed. Then, when you actually do go to see a play, the words can be quite difficult to understand. There is little action and what action there is, is hard to understand. Noh has many barriers to it. But, what I feel is that in actually practicing it, it is not really that difficult. Noh deals with humanity, and perpetual themes, such as the love between parents and children, the mind of the lover, justice and righteousness between lords and vassals. In that sense, it is more natural than Kabuki and other plays that have terrible, contrived stories, such as where someone has to poison his or her own child to prove loyalty. Noh has nothing unnatural about it and this is something I want people to understand.

But Noh performers would tend to say, “You don’t need to understand it; just enjoy the atmosphere.” Academics, on the other hand, like to dig deeper and refer to such things as original sources. I just wanted to make Noh interesting and accessible to the layman, and, by reading about a play, be able to understand the keypoints of it, what they need to know. My role is a kind of interpreter. I have been engaged both in Japanese literature and actual Noh performances, on and off the stage. I am a player, a scholar and writer all at the same time. I think I have an obligation to to convey Noh to the average person in an understandable way. You could say it’s my mission.

Editor (M) : I’d like to say something in that regard. I brought some of your books home and intended to read them before I met with you. Then my wife, totally strange to Noh, happened to see them piled on the desk, picked them up and started reading. She was hooked in no time, they were so fun to read. She ended up saying “I want to see that Noh play” and commenting, “this one is so and this one is so…” She asked me to thank you on her behalf for writing such readable books. (laugh)

Hayashi : I am really happy to hear such a story. Naturally, I want people to find Noh interesting. Taking the easy way out and just saying, “Enjoy the feeling even if you don’t understand it” or, “Look at the costumes. They’re so beautiful,” is a little bit irresponsible in my opinion.

Editor (F) : If you go to see Noh thinking such, you may end up only going once.

Hayashi : That’s true. You may not understand how interesting it really is. I want to implore people to watch Noh much more seriously, much more earnestly. Noh has been refined over hundreds of years. Watching it just for the feeling is a shame. That’s not right. Instead, I think people should take Noh very, very seriously, such as the English regard Shakespeare.

The unskilled should model themselves on the skilled and the skilled should model themselves on the unskilled

Editor (F) : In addition to being engaged in actual performances, you also have a career at Tokyo University of the Arts teaching budding Noh performers. Can you please tell your expectations for the Noh society, including a message for the next generation of Noh performers.

Hayashi : The students I met at Tokyo University of the Arts were all serous-minded and pleasant enough. What I expect them and other Noh performers is to be aware of is that Noh is both a performing art and literature at the same time. Most Kabuki and Joruri texts are not all that interesting or amusing to read. But a Noh performance is very powerful as an epic tale. For this reason, I would like Noh performers to fully understand the content and the settings of the plays a well as the message they convey, rather than simply repeating things learned from their masters. I want them to study and perform with their own interpretation. I believe that plays developed in such a manner will live on as have the achievements of masters of all times.

I have sat in backstage and watched a late famous Noh performer watch from behind the curtain, with his eyes riveted on another performer on stage. Really top-notch performers will study the performances of other players in such a way. Zeami also says that the unskilled should model themselves on the skilled and the skilled should model themselves on the unskilled. While it is quite natural to watch and study plays performed by skilled masters, the very same masters may learn something from watching the performances of younger players. In that sense, I would also like them to carefully read Zeami’s books and perform Noh plays after further study and after acquiring more knowledge. That’s my biggest hope.

(March, 2008)

Profile

Born in Tokyo in 1949. Writer/bibliographer. Ph.D. from Keio University. Served as visiting professor at Cambridge University (UK) and assistant professor at Tokyo University of the Arts, among others. Specialized in Japanese bibliography and literature. Was recipient of the Nihon Essayist Club Award for “Igirisu wa Oishii (U.K. is Delicious)” and Japan Foundation’s Encouragement Prize for “Early Japanese books in Cambridge University Library.” In addition to writing, Hayashi is active in diverse fields, including Noh theatre, poetry composition and cooking. He also performs extensively these days as a baritone singer. Has written a number of books including “Geijutsuryoku no Migakikata (How to Enhance your Art Power),” “Tokyo Botchan,” and “Satsuma Student, Nishi-e (Satsuma Students, Go West).”

Books on Noh include “Noh-wa Ikiteiru (Noh is Alive),” “Surasura Yomeru Fushi-kaden (Reading the Fushi-kaden),” and “Korenara Wakaru Noh-no Omoshirosa (Finding the Fun of Noh).”

| Terms of Use | Contact Us | Link to us |

Copyright©

2026

the-NOH.com All right reserved.