|  |  |

| | Home | Cultural Exchange | Chamberlain (2) |

FEATURE:Noh and International Cultural Exchange

6The Legacy of Ernest Satow

Satow Often Attended Noh and Collected Utaibon

It was eleven years before Chamberlain came to Japan. In September of 1862 (Bunkyu 9), an English diplomat came to Japan as an interpreter. That diplomat’s name was Ernest Satow, and at the time he was only 19. Satow is of course a very Japanese-sounding name, as if perhaps his ancestors were Japanese or he had perhaps changed his name. But Satow was actually the surname of his Swedish father, and he had no connection to Japan. However, when he came to Japan, he adopted the Japanese kanji “Sato” in writing his name. After that he married a Japanese woman with whom he had children.

Satow experienced first-hand the Namamugi Incident (1862), the resulting Anglo-Satsuma War (1863) and the Bombardments of Shimonoseki (1864), and he also developed friendships with the nationalists who supported the Meiji Revolution. He was truly a living witness to the end of the Japanese Shogunate, looking on the events of the time as an outsider. He was also actively involved in the revolutionary events taking place within Japan at the time. He worked for quite some time as the secretary for the British ambassador to Japan Harry Parks, after which he himself became ambassador to Japan and lived there for 25 years, authoring many works in his time there. Satow also played the role of introducing Japan and Japanese culture and the vibrant history of the country from the time of the end of the Shogunate through the Meiji era.

Satow, who captured this period of history from the perspective of a foreigner, is well known in Japan, but what is not well-known is Satow’s interest in Noh. He began taking notice of Noh from the end of the Shogunate, regularly attended performances, and collected utaibon. After the age of missionaries in Japan, Satow may have been the true initiator of the study of Noh by foreigners and exchange between Japan and the outside world. A record remains of Satow’s visit to a Noh performance by Tayu Kongoh’s, and from this we know that Satow was known in Japan at the time as an Englishman with an interest in Noh.

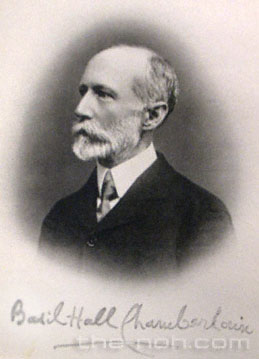

Chamberlain was friends with Satow. Satow knew that Chamberlain had a love of Noh, and when Satow left Japan, he gave Chamberlain the hundred or so utaibon he had collected over the many years. As such, Chamberlain’s study of Noh was also supported by this friendship.

Chamberlain’s Legacy

©AichiUniversity of Education

One of Chamberlain’s students was Nobutsuna Sasaki, a scholar of Japanese literature. While he was not educated directly at university, he received very close teaching from Chamberlain. When Chamberlain himself left Japan for Geneva, this time he gave the utaibon Satow had given him to Sasaki. According to Sasaki, many of these were rare books hidden from the world. He considered them living keepsakes from Chamberlain, and published them as Shin-Yōkyoku-Hyakuban (“A New Collection of Noh Chants” [unofficial translation]) in 1912 by Hakubunkan. This collection includes a preface from Chamberlain, and the original utaibon that form its contents were passed down as gifts from Satow to Chamberlain to Sasaki.

Chamberlain, a pioneer among foreign researchers of Noh, carried on Satow’s accomplishments, sharing them openly with his Japanese students. What Chamberlain, who built the foundation for later generations, gave us was not only the historical value of the utaibon, but also his honest, profound and scholarly disposition.

Enjoying Chamberlain’s Translations

Following is one of Chamberlain’s actual utaibon translations, “The Robe of Feathers.” The style is very different from modern English, and it is at best an approximate translation, but from it you should be able to enjoy Chamberlain’s sense of poetry.