|  |  |

| | Home | Cultural Exchange | Introduction |

FEATURE:Noh and International Cultural Exchange

1Introduction to Noh around the World

The history of the introduction of Noh art to the world is briefly described here. The-Noh.com will select remarkable themes and figures and improve this content based on this brief history.

Noh Originated Outside of Japan

Noh and Kyogen originated in sarugaku (humorous mime), which derived from a performance art born overseas. The performance art of sangaku, which traveled all the way from Persia over the Silk Road, finally arrived in Japan and turned into sarugaku. Sarugaku incorporated various forms of performance art, repeatedly sophisticated itself, and developed to the Noh art of today.

Considering such historical background, it could be said that Noh originally possessed universal characteristics, which are easily accepted by people all over the world. Looking upon Noh stories leads us to meet human emotions and philosophical questions, depicted in the drama. Not only the Japanese but other ethnic groups around the world would be able to similarly experience the earthy human emotions and deep thoughts expressed in the Noh world.

It is not surprising that Noh actually has a long history of international relations. In the late 16th century (the Adzuchi-Momoyama era), Noh had already appeared in the records of Christian missionaries in Japan. Also, it was introduced in China in the same period. Many feudal lords of the era, including Toyotomi Hideyoshi who reunified Japan, admired and danced Noh.

It was therefore natural for the missionaries, who worked close to these feudal lords, to become familiar with Noh art.

Noh Study in Western Countries Developed in the Meiji Era

It was the late 19th century (Meiji era) when Noh took its veil off again for people outside of Japan. Due to the Meiji Restoration, Noh and Kyogen were ousted from their position as the official ritual music of Edo Shogunate and experienced a crisis. It however survived these hard times, actively supported by dignitaries of the new government and other leading figures and was gradually revived.

In the reviving process, several foreign teachers, who had been visiting Japan, encountered Noh art and were impressed. Some of them started to study the literary research of Noh art, and others even started to learn how to perform Noh. Since the Japanese government frequently hosted Noh performances to entertain guests from overseas, it would be reasonable to say that foreigners in Japan at that time had significant opportunities to be exposed to Noh.

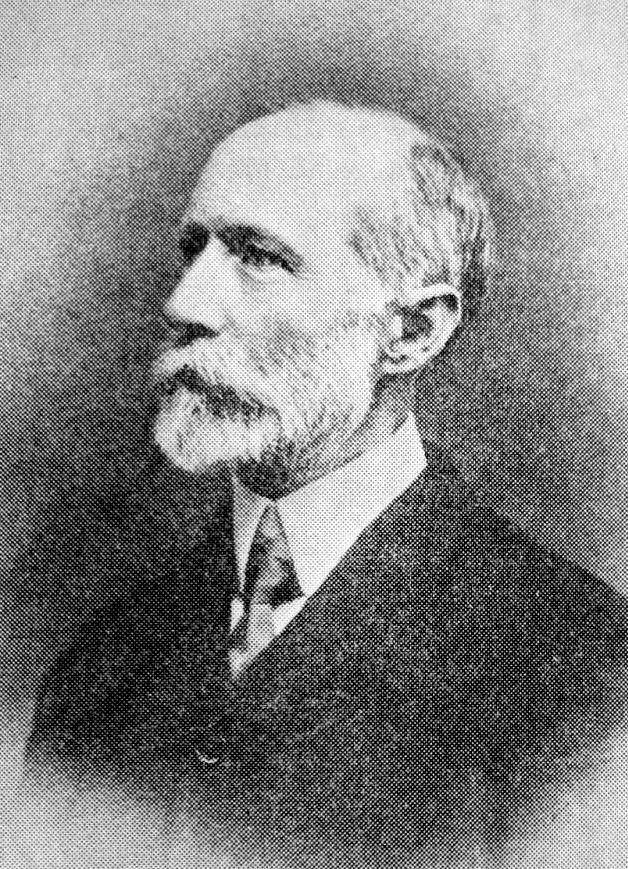

Basil Hall Chamberlain, who left great marks on the study of Japanese culture, is representative of British scholars of Japanese studies. He taught Japanese linguistics at Tokyo Imperial University (present Tokyo University) and was good at making Japanese poems. He produced a scholarly publication recognizing that Noh dramas were excellent poetic literature. In addition to Chamberlain, Frederick Victor Dickins, a British military doctor, and William George Aston, a British diplomat, published their work on the study of Noh art. Ernest Mason Satow, a well-known figure who had worked in Japan as a diplomat and interpreter of British minister for many years following the end of the Edo era, was another person enchanted by Noh.

Among the Americans, Edward Sylvester Morse, highly-reputed zoologist, was also fascinated by Noh. He practiced Noh chanting as a disciple of Umewaka Minoru. Furthermore, Morse's friend, Ernest Francisco Fenollosa, a great figure who did impressive work in the field of research on Japanese art, was also possessed by the charm of Noh. He became a disciple of Umewaka Minoru, introduced by Morse, and learned Noh chant and dance. Fenollosa's study of Noh art was superb. After his death, his work was published in the Taisho era (1912-1926), supported by valuable efforts of Ezra Pound, an American avant-garde poet. Ezra Pound was captivated by a famous Irish poet, William Butler Yeats and introduced Noh to Yeats. In later years, Yeats published a stage play, At the Hawk's Well (1921), inspired by Noh. Yeats' At the Hawk's Well was brought back to Japan in the Showa era (1926-1989).

From the end of the Meiji era to the Taisho era, a French missionary, Noel Peri, and Arthur Waley, curator at the British Museum and translator of The Tale of Genji into English, also made significant contributions in translating Noh dramas. Also around this time, the Japanese started to introduce Noh in English. Ikenouchi Nobuyoshi and Maruoka Katsura, who supported Noh art from various perspectives, devoted pages to English description of Noh in their magazines.

Paul Claudel, a French Symbolist poet and playwright who visited Japan in the Taisho era, became a diplomat, because he wanted to come to Japan. After reaching Japan, he exposed himself to various Japanese arts and deepened his knowledge of Noh as well. His writings closely grasp the nature of Noh, and his insight into Noh has been reflected in his poems and stage plays. Claudel's work is distinctively coruscating in the world of Noh.

The First Performance Outside Japan - Venice, Italy 1954

After the Second World War, Noh approached the outside world in a different style. Before the war, publications played a major role in introducing Noh to the world outside of Japan. On the other hand, after the war, Noh began to be often performed in foreign countries, which provided more chances to the people around the world to enjoy the art of Noh.

The first Noh performance in a foreign country happened at the music festival in the Venice Biennale in Italy in the summer of 1954. It was an unprecedented event in the history of Noh: the first time it was performed in full on foreign soil. The mixed group of the Kita and Kanze schools danced on the special stage assembled for their performance. Their performance was broadcasted on television in Italy. They achieved a great success, which led them to have another overseas performance at a cultural festival in Paris three years later. After the event in Paris, Noh expanded its field of performance to other European nations, the United States, countries in South America, the Middle East, and South East Asia, India, China, and Korea.

Including Kyogen, each Noh school energetically organizes its own or collaborative performances with other schools outside Japan. Thanks to these efforts, people all over the world can directly experience and enjoy the profound world of Noh: delicate human emotions, the deep philosophical world of Buddhism, and densely expressed nature of Japanese culture, all of which have been handed down through the art of Noh.

Today, some people who were born outside of Japan thoroughly engage in the practice of Noh, perform Noh dances, and receive certificates to teach Noh. In the future, more people around the world will become enchanted by the art of Noh and bring fresh breezes to its tradition.